4 Fundamental Observations on Skill Development in 6-to-9-Year-Old Athletes

By Phil Hueston, NASM-PES; IYCA-YFS

Our fitness business and facility has what we call a “blended” clientele. Part of our clientele is made up of adults seeking to lose weight, reduce body fat, improve their health, and generally train for life itself. Some are here to prepare for athletic events of various natures: 5K and 10K runs, mud runs, Spartan Races, and other socially competitive events dominate the list. Some wish to compete at high levels in team and individual sports: Triathlons, marathons, adult sports leagues, and strength competitions are some examples. These adult athletes seek greater levels of fitness specificity than most and tend to be educated about their sport and the fitness required.

A handful of our adults are professional athletes. These athletes pursue their fitness like it is their job because, quite frankly, it is. Highly specialized programming with more sport specificity and an ability to react and respond to their sport-skill training needs is typical of our work with these athletes.

We also enjoy a large population of youth athletes, “mathletes” and “non-letes.” These vary in age from 6 to 21 and come in all shapes, sizes, and athletic abilities. From the fun-loving 6-year-old to the budding scholarship athlete, our facility enjoys a variety of under-21 fun-loving bipeds.

I’ve been paying attention lately to how various types of athletes process skill development activities, efforts, and feedback. In this piece, I’m sharing some of those observations, what I believe they mean, and how you might benefit from recognizing some of what I’ve seen.

Youth Athletic Skill Development

It is important to define what we mean by “skill development” here. I’m talking specifically about physical skills, or what I call “athletic adaptation skills.” These are the movement skills required to complete certain training and exercise activities with proper form repeatedly so that the intended training affect can be successfully attained.

Strength and power activities require appropriate levels of joint stability (static, transitional, and dynamic), deceleration skills, and active and passive alignment skills. Speed and agility activities require high levels of dynamic joint stability, muscle elasticity and response, and maximal levels of spatial and kinesthetic awareness.

Each aspect of the “athletic skill-set” (defined by us as strength, power, speed, agility, quickness, balance, coordination, mental acuity, and tactical decision-making) requires certain athletic adaptation skills in order to properly develop them. This article will address some observations and ideas regarding athletic adaptation skills in the 6-to-9 age group.

Herding Ferrets

In the 6-to-9-year-old age range (IYCA “Discovery” age group), here’s some of what I’ve noticed. First, this age group doesn’t respond well to highly rigid, complex skill development programming. Duh. We’re dealing here with a group of children who’ve only recently gone from having relative freedom of movement, thought, and emotion to being told “sit down and be quiet and learn this stuff we’re shoving in your head. No more fun thoughts.” Imagine how much pent-up energy gets attached to the feeling of being stuck in these young athletes. No wonder starting school can be so traumatic for many children!

For kids up to about the age of 4 or so, the vast majority (some say as much as 80%) of their thought is imaginative and creative in nature. They create entire stories and worlds out of their thoughts then play and act in, around, and through them. They design free-flowing games with no, few, or very fluid rules. They enjoy large measures of movement freedom with little or no purposeful correction or instruction (“No! Don’t touch that!” doesn’t really count here), and we, as adults, tend to physically interact with them in ways that match their movements and play desires.

Suddenly school introduces a rigid and structured environment—arguably necessary under the current goal-structure of most curricula—in which imaginative thought has less value than mastering pre-determined lessons and filling the head with “brain stuff.” Add to this the massive developmental leap asked for in most youth sports at this age, and we’re talking about a brain full of screaming monkeys!

So by the time they get to us, the youth fitness professional, we often feel like we’re “herding ferrets.” So how do we teach athletic adaptation skills and functional sports movement to these kids when the very system we need to tap is already overloaded and rebelling?

We don’t. At least not in the traditional sense. We’ve realized a few things about improving movement patterns in kids aged 6 to 9. In no certain order, here are some of them.

Insight 1: They don’t care about functional movement patterns.

You were done at the “fun” in functional. Deceleration skills? Nope! Change of direction skills? Nope again! Lumbo-pelvic hip alignment and glute activation? Hey, look! A chicken!

The few athletes in this age group who are interested in the science-y part of what you know either are mentally and/or emotionally developed beyond their years and driven by “those” parents (you know who I mean!), or are future serial killers. OK, that last one might be an exaggeration, but you get my point.

Bottom Line: If it ain’t fun, you ain’t gonna get ’em to do it, let alone do it repeatedly.

How to Get It Done: Take every functional movement and every athletic adaptation skill you want to develop and figure out how to put the 6-to-9-year-old child in a position to succeed at it! You see, when you do this, they begin to proprioceptively create patterns within their brains that reinforce what it should feel like. An added bonus to this is the visual mirroring that takes place as groups of kids get good at the movements. When other kids see good patterns, guess what their brains try to reproduce?

Get them to repeat it by making it fun! Any movement skill can be taught, developed, and reinforced faster and better if the process is fun. We’ve discovered that our 6-to-9-year-olds LOVE to run in bands! So, when we want to “teach” good running form, we build it into a series of “can you do this?” type of layered cues designed to elicit a form and movement response that helps develop good sprint and running skills.

Insight 2: They don’t love “the grind,” no matter what Dad says.

While you and I might really enjoy a good, challenging squat workout or deadlifting until we’re spent, I feel really confident saying that your 6-to-9-year-olds don’t want to work until they feel like puking. That’s a fantasy world built by some coaches and dads who should be asked to stay in the car while their kids work out.

Do you know what many of them do love? They love the idea that they’re working hard! If you’ve structured a strength development activity to work on form or correcting alignment in such a way that 6-to-9-year-olds enjoy it, tell them what a great job they’re doing and how proud you are of how hard they’re working. Then go have more fun. Over time, working hard in this way will equate to fun.

How to Get It Done (1): Try the “Levels Game.” Put each kid in proper squat start position. Show them three different levels of squat depth, each with a number or letter designation. The goal is for them to hit each level on cue, while maintaining the exact foot, ankle, knee, and torso alignment you desire. Make up funny names for each position if you like. Play each round for 1-2 minutes. After 2 or 3 rounds, their legs will be feeling it. That’s the time to heap on the praise for sticking it out and “doing it better than the older kids.”

How to Get It Done (2): Try “Bear Crawl Bumper Pool.” Spread hoops around the floor of the workout area. With the kids in bear crawl position, you (or the coach) start by standing in a hoop. All the kids must keep moving and must keep their knees off the floor for the entire game. The kids count to 5, then you must move to another hoop. If they tag you on the way, they win. If one of the bears touches their knees to the ground or falls over, you win. You can play “one and done” or play for a set amount of time, keeping score based on the rules above. To increase the level or variety of athletic adaptation skills in this game, add an aspect of specific positioning to the crawl patterns, such as exact knee position (increased hip mobility) or change to a 2-foot hop movement with free moving arms (ankle mobility, core activation.)

In both of these games, the kids will end up “working hard” and having fun. Congratulate them on both!

Insight 3: They need to blow off steam!

Most of the time, you’re getting these 6-to-9-year-old bundles of energy right after school (you know, the “sit there and learn all this junk” experience). Recognize that and connect with them over it. Ask them how their school day went. Care about the answer. Then, turn them loose on the floor for 5 minutes of free play. You’ll get to see some unadulterated fun while you observe how their athletic adaptation skills are developing.

You may also get some great ideas for games. In our facility, we have a saying, “Put 3 kids on the floor with a ball and a new sport will be born.” That sport might only last 5 minutes or it might turn into something you play over and over.

How to Get It Done: Give the kids 5 minutes of free play before your planned session begins. Don’t have time in your programming for free play? Start your session with something goofy that they can win against you. Let them build their own obstacle course (talk about redirecting mental energy!) Let them play dodgeball. Remember, this is the time to re-set their brains for the activity to come.

Insight 4: They need validation and recognition!

These athletes are at a time in their lives when they are developing a vast set of physical, mental, intellectual, and emotional patterns, abilities, skills, limits, and tendencies. It’s also a time when they hear “no” an awful lot.

Think about it. Most coaches correct and coach with a “not that, this” approach. This begins with “no,” the one thing the child’s mind and emotions want to hear the least. I’m not suggesting you green-light total chaos or encourage selfish or destructive behavior; I am suggesting you remember that these kids are moving from the “pre-operational” stage to the “concrete operational” stage.

In the former, the child is still highly egocentric. In fact, empathy, which allows the child to consider the feelings and needs of others when responding to stimulus, planning activity, or deciding on actions, only begins to develop somewhere between the ages of 7 and 11, according to Piaget and others. Development of this response is considered part of the “concrete operational” stage, in which the child more deeply learns to interact with the world beyond parental and other institutionalized controls.

During this latter stage, hearing “no” more frequently is likely, since many new interactions will be occurring. When a child hears negative feedback and response to actions frequently, he/she is likely to take fewer risks (though their perception of their own actions is not one of risk or no risk, but just what they do). Since we need these kids to be willing to try in order to learn new skills, providing an encouraging environment where they expect “yes” is important.

One of the key areas in which a child 6 to 9 years of age needs to hear positive responses and validation of their worth relative to the activity at hand is in front of the parent(s). Assuring that the athlete’s parents hear you praising their child is more important to the child than the parent in most cases. The fact that it makes it easier to engage that parent in enrolling their child in your program is a bonus built of truth. Talking positively to the parent with the athlete present or within close earshot is also incredibly powerful in developing an achievement attitude.

How to Get It Done: Create “yes” situations for each degree of completion of an athletic adaptation skill acquisition activity. For example, if you are playing tag and an athlete is lined up to start, simply saying “perfect, you’re ready to go” is just the ticket. Once you’ve established this positive baseline, you can layer in more instruction and more complexity with an expectation of success.

If we’re working on a squat skill or activity, no matter what the movement looks like, we open with a positive phrase. Something like “awesome, now we’re getting somewhere” allows us to immediately layer in a cue like “now let’s add something new.” This lets us either add a new layer of challenge OR make a necessary correction while presenting it as a new challenge.

When working with agility ladders (we all know the 6-to-9-year-olds love them, no matter their skill level!), we’ll always have at least one activity that starts on the side of the ladder or in a particular foot position. When an athlete remembers to set up well, we make a big deal of it. When they don’t, we might tell them “I’m psyched you’re ready to go, now let’s get you even more ready” and move them to the correct position. “Remember?” “Great! Let’s go!” High five them and off they go.

Seeing Success with 6-to-9-Year-Olds

At the 6-to-9-year-old age range, we’ve found that athletic adaptation skills develop better when we plug those skills into the activities we know the kids will love. Just as important, it is critical that we find the ones they will repeat. While we joke about “herding ferrets,” the athletic adaptation skills developed at this age tend to stick. And that’s good, since they are moving into an age where they will have input and instruction from a whole lot of people with a whole lot of good intentions (mostly) and not a whole lot of working knowledge of human movement.

The other huge benefit of understanding these skill development details is the creation of the “I can’t wait to go” factor. When you gain the loyalty of 6-to-9-year-olds, you become their “3rd place.” And that is good for your client—and good for your business.

In the next article, I’ll address some of the things we’ve noticed with our “Exploration” athletes in the 10-to-13 age group.

Phil Hueston is the co-owner of All-Star Sports Academy and Co-Head Coach at Athletic Revolution – Toms River, NJ. He has been, and continues to be, a sought-after Sports Performance Trainer and Consultant to teams and athletes at the Youth Sports, high school, collegiate, and professional levels.

Since his entrance into the fitness industry in 1998, he has questioned the status quo, challenged the conventional wisdom of the fitness industry, and used the answers to make his clients better, bigger, faster, and stronger.

Not just another pretty trainer, Phil has been called a “master motivator and trainer of high school athletes” and a “key player in the Youth Fitness industry.” He works with athletes, “mathletes,” and “non-letes” from 6 to 18, helping them all reach their performance potential and maximize their “fun quotient.”

Phil recognized early on that the ONLY task of Sports Fitness Professionals is the improvement of their clients’ sports performance and their enjoyment of the process! He has worked with thousands of athletes, assisting them on their journeys to collegiate sports, Division I scholarships, pro and semi-pro sports careers, and even the first round of the NHL Draft.

Recently, Phil was named IYCA Member of the Year for 2012-2013. He has also co-authored two books, The Definitive Guide to Youth Athletic Strength, Conditioning and Performance, which reached #1 Best-Seller status in two separate literary categories, and The IYCA Big Book of Programs.

Coach Phil can be reached through his company’s website, www.allstarsportsacademynj.com.

It is no secret that the development of the young athlete is multifaceted and it is the responsibility of the coach and/or trainer to take into consideration developmental, physical, and psychological aspects of training.

It is no secret that the development of the young athlete is multifaceted and it is the responsibility of the coach and/or trainer to take into consideration developmental, physical, and psychological aspects of training.

3. Calisthenics: The simple stuff like we did back in P. E. Remember jumping jacks? How about the lost art of jumping rope? Calisthenics are a fantastic tool for warming up and coordination activities. Simple? Yes… but much more effective than jogging around a soccer field if the goal is to improve athleticism.

3. Calisthenics: The simple stuff like we did back in P. E. Remember jumping jacks? How about the lost art of jumping rope? Calisthenics are a fantastic tool for warming up and coordination activities. Simple? Yes… but much more effective than jogging around a soccer field if the goal is to improve athleticism.

Jeremy Frisch is the owner and director of

Jeremy Frisch is the owner and director of

Brett Klika is a youth performance expert and a regular contributor to the IYCA who is passionate about coaching young athletes. He is the creator of the

Brett Klika is a youth performance expert and a regular contributor to the IYCA who is passionate about coaching young athletes. He is the creator of the

Erica Suter is a soccer performance coach at JDyer Strength and Conditioning in Baltimore, Maryland. She works with youth athletes across the state of Maryland in the areas of strength, conditioning, agility, and technical soccer training. Besides coaching, she is a passionate writer, and writes on youth fitness as well as soccer performance training on her blog

Erica Suter is a soccer performance coach at JDyer Strength and Conditioning in Baltimore, Maryland. She works with youth athletes across the state of Maryland in the areas of strength, conditioning, agility, and technical soccer training. Besides coaching, she is a passionate writer, and writes on youth fitness as well as soccer performance training on her blog

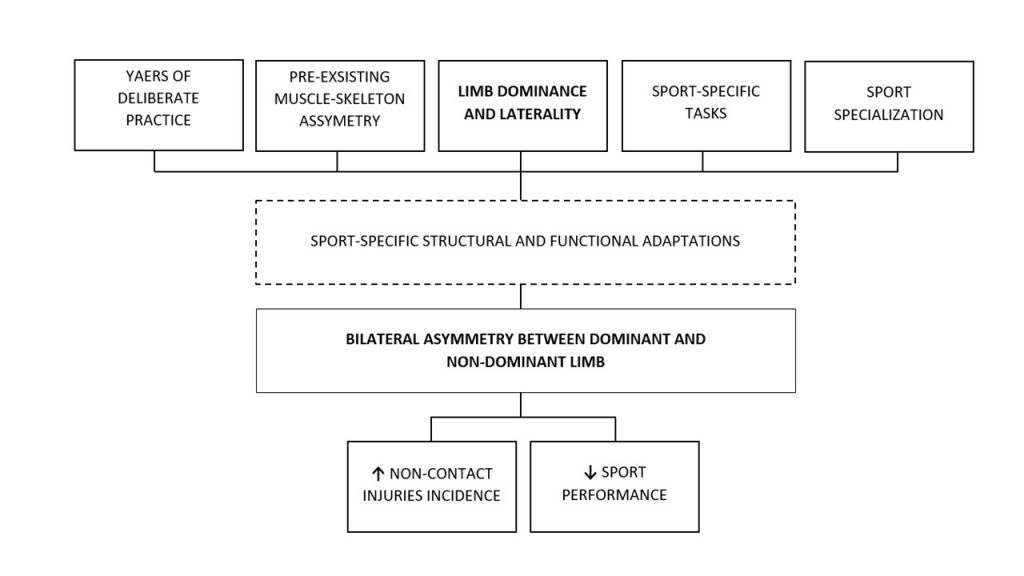

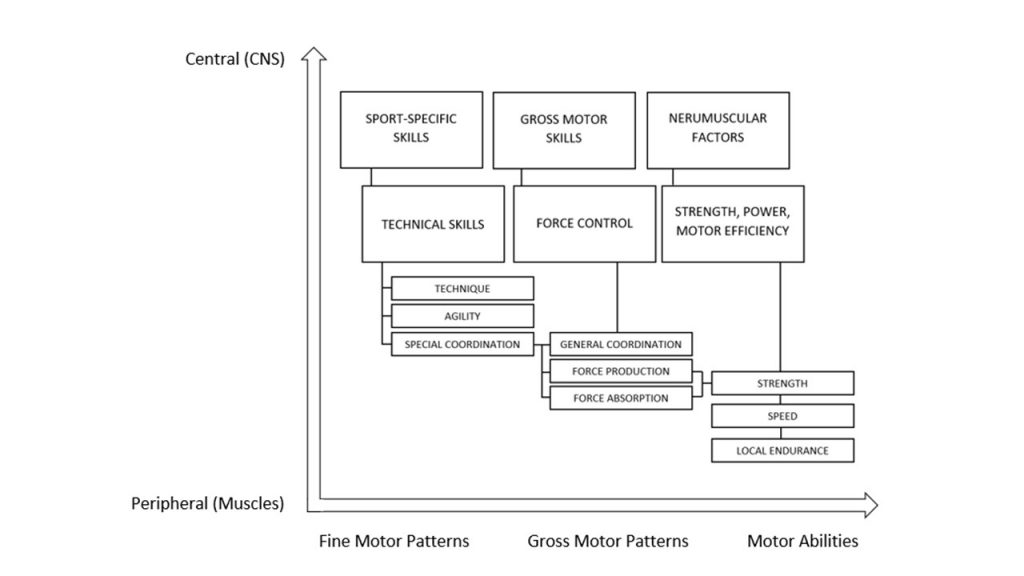

Examples are sport specific exercises involving acceleration, deceleration and change of direction drills (agility drills) performed in both an open and/or closed skill situation, linear and rotational throws and a wide variety of technical drills involving eye-hand and eye-foot coordination activities where the dominant limb is used according to the physiological preference of the athlete.

Examples are sport specific exercises involving acceleration, deceleration and change of direction drills (agility drills) performed in both an open and/or closed skill situation, linear and rotational throws and a wide variety of technical drills involving eye-hand and eye-foot coordination activities where the dominant limb is used according to the physiological preference of the athlete.

Antonio Squillante is the Director of Sports Performance at Velocity Sports Performance in Los Angeles, California. He is in charge of the youth development program which includes over 100 athletes 17 years old and under competing in many different sports. Antonio graduated summa cum laude from the University San Raffaele – Rome, Italy – with a Doctorate Degree in Exercise Science. He has worked in college and professional athletics, has written numerous articles and holds certifications from multiple organizations.

Antonio Squillante is the Director of Sports Performance at Velocity Sports Performance in Los Angeles, California. He is in charge of the youth development program which includes over 100 athletes 17 years old and under competing in many different sports. Antonio graduated summa cum laude from the University San Raffaele – Rome, Italy – with a Doctorate Degree in Exercise Science. He has worked in college and professional athletics, has written numerous articles and holds certifications from multiple organizations.