As an industry, we are playing a losing game right now and it’s time to look in the mirror. Consider this, if seven out of ten employees quit their job at a company due to burnout or overuse, it’s fair to assume the company would be concerned.

As an industry, we are playing a losing game right now and it’s time to look in the mirror. Consider this, if seven out of ten employees quit their job at a company due to burnout or overuse, it’s fair to assume the company would be concerned.

So what makes the youth sports industry any different…why aren’t we paying attention to our younger kids, seeing the red flags or doing something about this?

Perhaps some are, but it’s going to take MUCH more.

You may be wondering what we are talking about, and this is the first step…awareness. It starts here and in this article we hope to bring awareness to the problem and a staggering statistic that is plaguing our industry and setting our children and future generations up for failure.

In a recent study, by the American Academy of Pediatrics they stated that although over 60 million children and adolescents currently participate in organized sports, attrition rates remain staggeringly high, with 70% of youth athletes choosing to discontinue participation in organized sports by 13 years of age.

Look around your teams, training sessions and end-of-season parties, the likelihood is that 7 out of every 10 athletes will be done playing sports before they reach high school.

Most likely, the majority of those 70% will either get injured and sit or burnout and quit. This isn’t even considering the possibility that some athletes’ that remain playing, only do so because they feel they have to or are obligated to.

According to the study, the professionalization of youth sports is widely considered responsible and is a result of high volumes of training, the pressure to specialize which can increase odds of injuries, overtraining and burnout (2,3).

Burnout, however, is only one reason for dropout, others on the list include a loss of interest, lack of available time, interest in other activities, lack of playing time and lack of fun.

If you are reading these numbers as a coach, trainer, parent, athletic director or ANYONE who facilitates or coaches teams, we hope that it strikes a chord. Perhaps, even, there may be doubt about theses statistics?

If that is the case, don’t take it from us, get out there and educate yourself with credible resources and research.

In a take home message from Pediatric Child Health, participation in organized sports should be aimed at the developmental level (which may not be the ‘chronological age’) of the participants so that they enjoy being physically active. (2)

Children should be encouraged to participate in a variety of activities and avoid early specialization.(2)

Parents can be instrumental in promoting physical activity and sport participation in their children by ensuring that children are having fun at their development level. To provide a basis for lifelong involvement, parents and coaches should strive to provide positive sport experiences for children that match their interests and developmental capabilities. (2)

We hope you are asking…how do we fix this?

This is a question we’ve been asking for years, and the truth is, we need to take an all-hands-on-deck approach to reverse these trends.

We must change as a collective industry if we want to move toward a more sustainable direction for our young athletes. Parents, sport coaches, trainers, sport organization officials and schools must collectively come together and collaborate versus compete. We must work in synergy, not against each other, and we must keep the athlete a priority.

Are you with us?

So, where do we go from here?

There are some STOPS & STARTS we recommend so we set our future athletes up for the WIN not just in sport, but in life well into adult-hood.

1. START teaching foundational and functional skill development while promoting a well rounded approach to their overall development as an athlete respective to their athletic & developmental age. (Learn more about Long Term Athlete Development and Physical Literacy and how to do this)

2. START facilitating workouts & practices that are engaging, memorable and exciting with age appropriate games and training to keep sessions and practices engaging and FUN. (See the Long Term Athlete Development Model)

3. START encouraging and planning for athletes to take adequate time off- at least 1 or 2 days a week- to rest and recover.

4. STOP encouraging athletes to specialize, defined as: “year-round intensive training in a single sport at the exclusion of other sports.”(3) START taking OFF 2-3 months (they don’t have to be subsequent) from individual sports..

5. START supporting athletes’ in playing another sport while taking a ‘break’ and/or START seeing a Certified Performance Coach who is Certified to teach Long Term Athlete Development and Physical Literacy principles. (Recommended Certification)

6. START emphasizing and celebrating athletes in their process goals vs their performance outcomes.

7. START prioritizing the WHOLE athlete. Encourage mindfulness and emphasize overall habits of athletic health (Hydration, Nutrition, Sleep, Mindset, Motion, Relationships, etc). Seek out or become a specialist beyond the ‘skill of the game’ when needed.

8. START implementing the Long Term Athlete Development Model and reinforcing Physical Literacy principles or seek out a performance professional who is Certified to Coach athletes at their developmental and athletic ages, which could be different than their chronological age. (Recommended Certification).

9. STOP coaching all athletes the same. START understanding how they need to be coached to be most successful, and adjust to meet them where they are at.

10. Lastly, START 1-9 as soon as possible!

There is no doubt that involvement in sports can be extraordinary and positive experiences for young athletes, but we have a long way to go in providing these experiences consistently. We believe that this should be the duty and mission of every Sport Coach, Sports Organization, Athletic Director, Performance Professional and Parent.

As an organization, The IYCA strives to positively impact the healthy living habits and behaviors of tomorrow’s generation. We know that developmentally-sound, purposeful, and fun movement exposures provided through conditioning, fitness and sports are critical building blocks in developing from the younger years and well into adulthood.

The first step is awareness, then education and action!

We know that some may read this right now and not take action, but some of you will be ready to join this mission and take action. If that is you, keep reading! Below are two of our best resources that will start to bridge the gap that is causing our athletes to drop out, burnout and lose.

If you are a community builder and want to play your part in reversing this staggering trend in your community, then the IYCA Certified Athlete Development Specialist is the perfect stepping stone to furthering your knowledge in order to provide extraordinary long-term experiences for the athletes you work with.

If you are looking to learn more and further your knowledge on how to develop athletes long term in a healthy and appropriate way but aren’t in need of a certification, then a great next step would be Long Term Athlete Development: The Lifelong Training Roadmap

If you are looking to learn more and further your knowledge on how to develop athletes long term in a healthy and appropriate way but aren’t in need of a certification, then a great next step would be Long Term Athlete Development: The Lifelong Training Roadmap

Now, let’s go WIN THIS game!

– The International Youth Conditioning Association

References:

1. Joel S. Brenner, MD, MPH, FAAP; Andrew Watson, MD, MS, FAAP; COUNCIL ON SPORTS MEDICINE AND FITNESS https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/153/2/e2023065129/196435/Overuse-Injuries-Overtraining-and-Burnout-in-Young

2. Sport readiness in children and youth. Paediatr Child Health. 2005 Jul;10(6):343-4. PMID: 19675844; PMCID: PMC2722975.

3. Jayanthi N, Kleithermes S, Dugas L, Pasulka J, Iqbal S, LaBella C. Risk of Injuries Associated With Sport Specialization and Intense Training Patterns in Young Athletes: A Longitudinal Clinical Case-Control Study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020 Jun 25;8(6):2325967120922764. doi: 10.1177/2325967120922764. PMID: 32637428; PMCID: PMC7318830.

Coaches may recognize an exaggerated arch in the lower back, but that’s just one part of the equation. The ability to control anterior and posterior pelvic tilt is critical to sprinting, squatting, hinging, and a variety of athletic movements. Many athletes struggle with these movements because they simply don’t know how to create or control pelvic tilt.

Coaches may recognize an exaggerated arch in the lower back, but that’s just one part of the equation. The ability to control anterior and posterior pelvic tilt is critical to sprinting, squatting, hinging, and a variety of athletic movements. Many athletes struggle with these movements because they simply don’t know how to create or control pelvic tilt. Jim Kielbaso is the President of the IYCA and owner of

Jim Kielbaso is the President of the IYCA and owner of

When it comes to the squat, the deficits are typically the knees moving forward excessively as well as moving inward.

When it comes to the squat, the deficits are typically the knees moving forward excessively as well as moving inward.

Tears rushed down my cheeks and fell to the grass like the collective sweat that rushed down our necks. I wanted to be inside the lines again. I yearned to still be a part of our sacrifice. To be living the collective commitment we made to one another. To be on the field playing the game that we loved. In those final moments, I was flooded with a sense of loss.

Tears rushed down my cheeks and fell to the grass like the collective sweat that rushed down our necks. I wanted to be inside the lines again. I yearned to still be a part of our sacrifice. To be living the collective commitment we made to one another. To be on the field playing the game that we loved. In those final moments, I was flooded with a sense of loss.

I found so much meaning in, I drew so much of my self-worth from sports. And while I found so much of myself

I found so much meaning in, I drew so much of my self-worth from sports. And while I found so much of myself  Jill Kochanek is a doctoral student at the Institute for the Study of Youth Sport at Michigan State University. She is also a high school soccer coach. As a coach-scholar, Jill is passionate about bridging the research-practice gap to make sport a more inclusive, empowering context. Her research and applied work centers on helping athletes (and coaches) take charge of their own developmental process and social progress. If you enjoyed this article, feel free to visit her youth sport coaching blog,

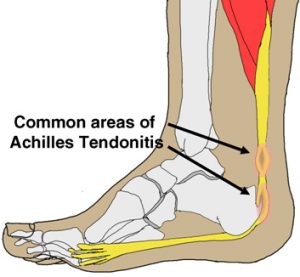

Jill Kochanek is a doctoral student at the Institute for the Study of Youth Sport at Michigan State University. She is also a high school soccer coach. As a coach-scholar, Jill is passionate about bridging the research-practice gap to make sport a more inclusive, empowering context. Her research and applied work centers on helping athletes (and coaches) take charge of their own developmental process and social progress. If you enjoyed this article, feel free to visit her youth sport coaching blog,  stress, which can easily lead to injuries and compensations.

stress, which can easily lead to injuries and compensations. Jordan Tingman – CSCS*, USAW L1, ACE CPT, CFL1 is a graduate of Washington State University with a B.S. in Sports Science with a Minor in Strength and Conditioning. She completed internships with the strength & conditioning programs at both Washington State University and Ohio State University, and is currently a Graduate Assistant S & C Coach at

Jordan Tingman – CSCS*, USAW L1, ACE CPT, CFL1 is a graduate of Washington State University with a B.S. in Sports Science with a Minor in Strength and Conditioning. She completed internships with the strength & conditioning programs at both Washington State University and Ohio State University, and is currently a Graduate Assistant S & C Coach at

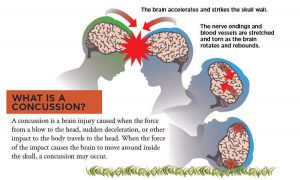

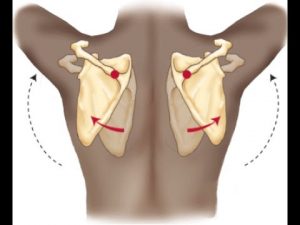

That’s why we see things like 12-year-olds getting Tommy John surgery or 13-year-old soccer players with hip dysplasia. These things are typically a result of athletes being pushed too hard, too early. They “appear” to be able to do things that they simply shouldn’t be doing yet, like throwing 80 MPH at 12 years old.

That’s why we see things like 12-year-olds getting Tommy John surgery or 13-year-old soccer players with hip dysplasia. These things are typically a result of athletes being pushed too hard, too early. They “appear” to be able to do things that they simply shouldn’t be doing yet, like throwing 80 MPH at 12 years old.

of strength and conditioning on social media. You’ll be much more inclined to find strength coaches showcasing impressive feats of strength, power, speed or even balance. How often do you see coaches talking about amazing flexibility routines?

of strength and conditioning on social media. You’ll be much more inclined to find strength coaches showcasing impressive feats of strength, power, speed or even balance. How often do you see coaches talking about amazing flexibility routines?

Instead of looking at what the pros are doing NOW, look at what they did when they were your kid’s age. This will give you insight into what helped them develop the foundation of athleticism they have today.

Instead of looking at what the pros are doing NOW, look at what they did when they were your kid’s age. This will give you insight into what helped them develop the foundation of athleticism they have today.

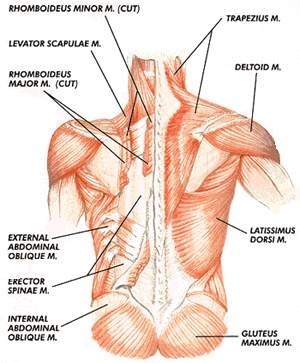

It is very common for athletes to experience lower back pain, especially when they begin a new training program or train harder than they have in the past. As muscles get sore and/or stiff from training, they will “hold onto” certain positions as a way to maintain different positions. Often, tightness in the internal hip/back muscles throws postural alignment off, which can lead to even more pain. This pain can be felt in various parts of the spine, but in this article, I will mostly focus on stretching muscle groups in the hips and lower back.

It is very common for athletes to experience lower back pain, especially when they begin a new training program or train harder than they have in the past. As muscles get sore and/or stiff from training, they will “hold onto” certain positions as a way to maintain different positions. Often, tightness in the internal hip/back muscles throws postural alignment off, which can lead to even more pain. This pain can be felt in various parts of the spine, but in this article, I will mostly focus on stretching muscle groups in the hips and lower back.