The concept of long term athlete development (LTAD) has been around for several years, but it has more recently become a hot topic amongst youth sports and training organizations. It seems that everyone now needs a formula for how to develop great athletes so they can represent their countries and succeed as professionals. Several academicians have taken the lead on reviewing the relevant literature and have written articles and books about the topic. They have used this literature to create several different models for developing athletes. While these models were a great start, their oversimplification of athlete development seems to be steering coaches, trainers and parents in the wrong direction.

To begin, the entire premise of LTAD theory needs to be examined. When it originated in the late 1990’s, academician Istvan Balyi identified some very important issues in many countries and sporting organizations, so he created a 3-stage model that emphasized long term athlete development over winning competitions. This premise challenged the approach of many coaches and got a lot of people to open their eyes to the problems in youth sports.

identified some very important issues in many countries and sporting organizations, so he created a 3-stage model that emphasized long term athlete development over winning competitions. This premise challenged the approach of many coaches and got a lot of people to open their eyes to the problems in youth sports.

Balyi’s original model included three phases – Training to Train, Training to Compete and Training to Win. A few years later, he realized that a fourth stage – FUNdamentals – should be added to address the fundamental motor skills that should be developed early in a child’s life.

Sporting organizations latched on to this theory and quickly started talking about it as a formula that would create great athletes. As these theories picked up steam, other academicians decided to jump on the train and create their own models. They included talent identification, more in-depth discussion on early childhood, and there was a strong emphasis on taking advantage of hypothetical “windows” of opportunity where different training methods would supposedly have a greater impact. The models told coaches when to emphasize strength training, speed training, endurance training and when to emphasize competition vs. training.

Eventually, some groups realized that an LTAD approach may also give children great sporting experiences that would lead to lifelong enjoyment of physical activity. Because of the childhood obesity and physical illiteracy epidemics, this idea seemed very attractive.

A few organizations came out with their own versions of LTAD that included 7-9 stages of development, and they felt good about adopting this approach because they believed it was the “right thing to do for kids,” even though it was nothing more than words on paper for most groups. These organizations would hire an expert to put together a model, but they didn’t seem to put much effort into the actual implementation. Education and coordination of efforts were left out of the models.

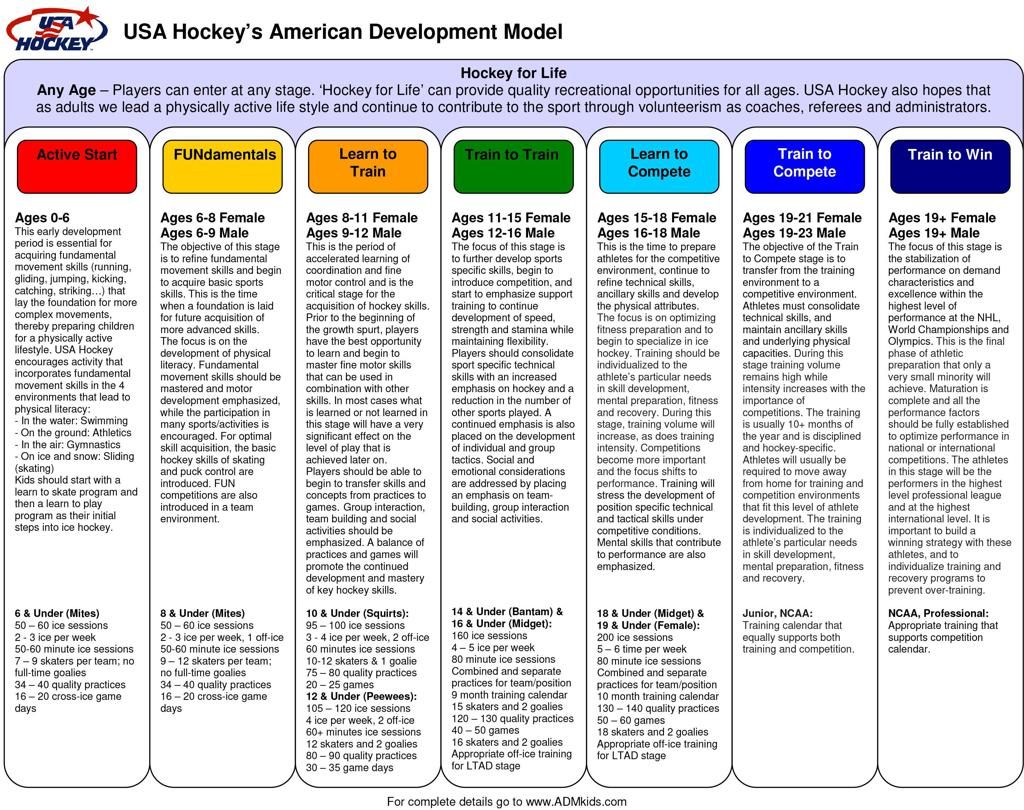

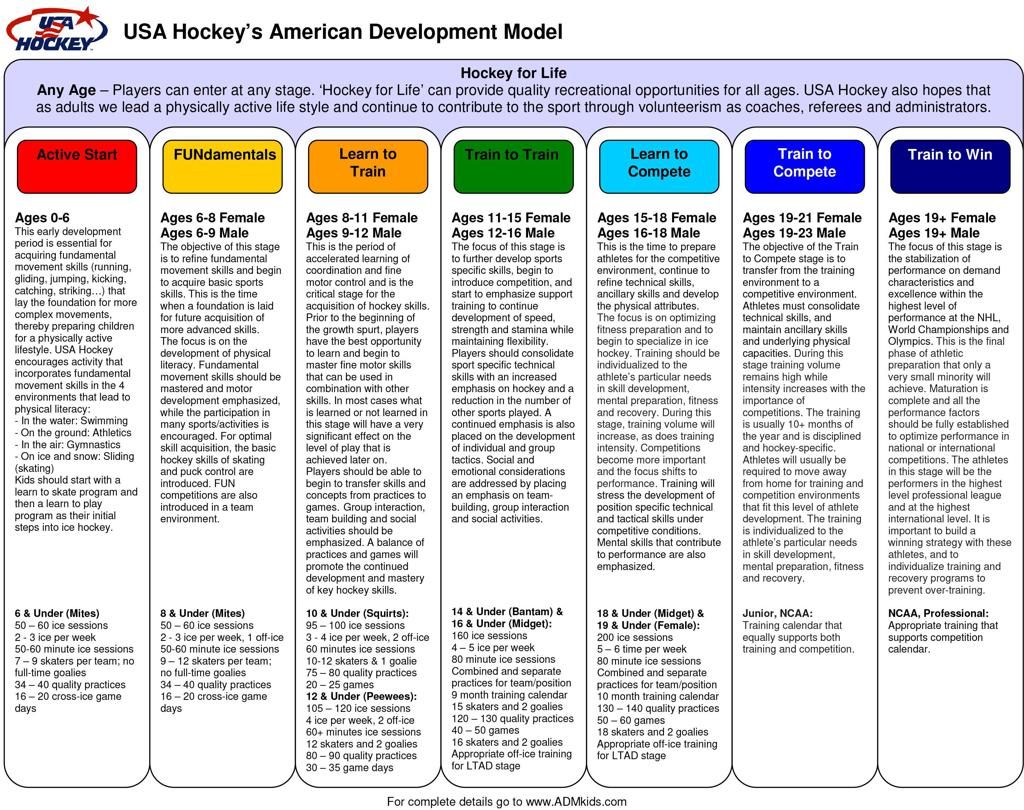

Eventually, the stages looked like this:

- Stage 1 – Active Start (0-6 years old)

- Stage 2 – FUNdamentals (girls 6-8, boys 6-9)

- Stage 3 – Learn to Train (girls 8-11, boys 9-12)

- Stage 4 – Train to Train (girls 11-15, boys 12-16)

- Stage 5 – Train to Compete (girls 15-21, boys 16-23)

- Stage 6 – Train to Win (girls 18+, boys 19+)

- Stage 7 – Active for Life (any age)

More in-depth models described when each training method would elicit the best results. USA Hockey did a much better job with their American Developmental Model that looked like this:

Still, a lot was left out, especially any details on implementation. For the most part, LTAD has remained theoretical, and implementation has largely been missing.

To be clear, the models aren’t necessarily “wrong” as much as they are incomplete and misleading. Most of them give the reader the impression that they have been thoroughly tested and proven, and that they contain a formula for success. This may not have been their original intent, but that’s how it has been taking by the sporting world.

The strength & conditioning/sports performance profession has taken notice more than just about any group because a lot of these models talk about “training” and “movement.” The term “athlete development” resonates with these professionals, so this is where many of the thoughts have become popularized.

These professionals have tried to implement these already-flawed, theoretical models by attempting to use different training methods at certain times to take advantage of the “windows of opportunity” outlined by academicians without coordinating their efforts with other important players in this process. This is one of the biggest mistakes made today, and the lack of integration with other groups has stymied progress and severely limited outcomes.

While the theory of long term athlete development is well-intentioned, the models have yet to produce exceptional athletes in real life. In fact, even the researchers admit that there was no real data to support any of the models. In a great review of some of the relevant literature, Guy Razi and Kieran Foy showed that the data does not support these models. It was all a great idea, but these models were nothing more than theoretical. To this day, no athlete has gone through the entire model the way it was originally laid out, and achieved a high level of success.

While the theory of long term athlete development is well-intentioned, the models have yet to produce exceptional athletes in real life. In fact, even the researchers admit that there was no real data to support any of the models. In a great review of some of the relevant literature, Guy Razi and Kieran Foy showed that the data does not support these models. It was all a great idea, but these models were nothing more than theoretical. To this day, no athlete has gone through the entire model the way it was originally laid out, and achieved a high level of success.

The models are also not very realistic in many situations. For example, the models include a lot of talk about peak height velocity (PHV) as the optimal time for the adaptation of certain traits. What is not addressed is how coaches are supposed to know when an athlete is experiencing PHV. In most sporting situations, kids’ height is not constantly monitored by coaches, and most of the training decisions described in the literature are related more to strength & conditioning than sports skills. Sports coaches might have contact with kids year-round, but most kids are not engaged in year-round strength & conditioning at an early age (this can be because of money, availability, beliefs, time restrictions, etc.). So, how would the strength coach know when PHV is occurring? It may not even matter since most performance coaches only see young athletes in limited spurts. Typically, parents come to a performance coach after PHV when they recognize altered movement.

If every child was in a “sporting academy” situation from a young age where they were constantly coached, trained and monitored, this may be possible, but it’s not realistic in most cases. An argument could be made that we should move toward these type of year-round academies so that everything can be monitored, but that’s beyond the scope of this article and it carries as many negatives as positives.

The most popular LTAD models propose “windows of opportunity” in which certain athletic traits may respond better to specific kinds of training. For example, it has been theorized that speed is best trained just before PHV, and that strength is best trained directly after PHV. These models lead many coaches to believe that worthwhile adaptation only occurs during these periods, and that is absolutely not true. Young athletes are always open to adaptation and can always enjoy the benefits of proper training no matter where they are in their maturation.

Every physical attribute can be trained at any time. Most practitioners just need to understand how to best address each attribute during maturation to achieve the best long-term and sustainable outcomes.

So, “missing” a window of opportunity does not mean progress in certain traits cannot be made. On the contrary, long term athlete development is much more individualized than these contrived models suggest.

Even more concerning is the fact that long-term implementation has not been thoroughly studied, which is ironic given the name of the theory and the fact that academicians created it. It is typically written/spoken about by people who do not coach athletes, have not successfully developed great athletes, and many don’t even have children of their own in which they’ve tested their theories or developed athletes into champions.

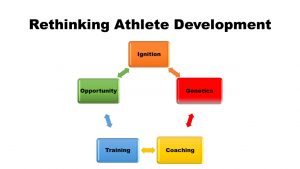

There are far too many factors involved in creating a great athlete to boil the process down to a few simple steps, and several key ingredients have been missing from the recipe. Developing athletes is highly individualized, and included many factors beyond those that are described in the current literature. These missing factors include:

- The child’s interest/passion for sport

- The psychological approach used with each athlete

- Parental support and their role in the process

- Environmental/societal influences

- Access to the coaching/training at the right time

- Genetic factors & talent identification

- Coordination of development with all parties (parents, coaches, trainers, etc.)

- Having the “right coach at the right time” or at least the right approach at the right time

Some of these factors cannot be easily controlled by coaches, rendering them “too messy” for academics to even attempt to address. Yet, these factors will determine the long-term outcome to a much greater extent than any theoretical model of when to train each physical component.

Kids are not robots, and developing athletes is not a science experiment.

We don’t need models – we need coaches….great coaches.

If we’re truly interested in developing great athletes and/or adults who enjoy physical activity, we cannot do it alone as strength & conditioning professionals. We must look at the entire picture, address physical, psychological/emotional and social aspects and include everyone involved in the development of the athlete – coaches, trainers and parents.

Much has already been addressed regarding the physical training of young athletes. The materials available through the IYCA and others are exceptional and give in-depth information on strength development, speed & agility training, flexibility/mobility, conditioning and even skill development. Rather than summarizing these methods, let’s explore the missing factors listed above and how each may be addressed.

Before we do that, two things need to be made clear:

- The term “youth” refers to anyone 18 and under. When people are first introduced to the International Youth Conditioning Association, they often assume we are focused on very young children. The process of athlete development begins at a very young age and continues until at least 18 years old, so it’s important for us to understand how to properly address each stage of maturation. Of course, athletes continue to develop past 18, but the process changes dramatically at that time.

- Great training and coaching are absolutely essential to the process of athletic development. This should be obvious, but it needs to be stated since it will not be addressed here. Training and coaching are addressed in many other IYCA materials and this is well beyond the scope of this article. Athletes need physical development, so speed, strength, sports skills, etc. are critically important. These topics are what most LTAD models focus on exclusively, and they should not be ignored.

Now, let’s examine the aspects of long term athletic development that are NOT included in most models, but must be understood if we are truly interested in overall development:

Passion

Enjoyment of sport is one of the most important underlying factors in long-term athletic success. If a young athlete does not find joy in a sport, the likelihood of him/her giving the long-term effort to excel is very small. He/she may go through the motions and experience some level of success, but it is very difficult for a young person to stay motivated to excel in a sport if passion is not part of the equation.

Without passion, the entire LTAD model comes to a grinding halt, so this cannot be ignored.

Without passion, the entire LTAD model comes to a grinding halt, so this cannot be ignored.

At some point, a child has to be willing to pursue a dream for themselves, not simply because he/she is talented or others want the success. In most cases, there needs to be a burning desire within a person if high levels of success are going to be achieved. Even more importantly, that passion needs to be fueled in order to sustain it long enough to achieve any real success. Playing for the wrong coach, not getting enough playing time, having poor teammates, lack of parental support and year-round play are some the reasons the flame burns out for many athletes. If the sport is no longer fun for a young athlete, it’s almost impossible to expect continued progress.

In his book The Talent Code, Daniel Coyle refers to a concept he calls “Ignition.” Essentially, this is what creates a deep passion for sport in an athlete. It might be exposure to a particular person, participation in an event, watching a sport, family involvement or something else. It will be different for every person, which is why this isn’t a formula. But, that ignition needs to exist if long-term success is the goal.

Parents, family and friends typically play the largest role in establishing a love for sport. Exposure to sports (live or on TV) and attitudes toward sports often start in early childhood. They can establish emotional feelings before they ever participate in a sport. There’s no right way for parents to approach sports with their children, but positive exposure to a variety of sports seems to be optimal.

As stated earlier, children are not robots, so there is no single formula for producing passion about a particular sport. Intense parental feelings about sports have the potential to influence children in both positive and negative ways. Some parents actually push kids away from sport because they are so passionate about it, while others create a healthy feeling of excitement.

Coaches and trainers often don’t even meet an athlete until some amount of exposure to a sport has been made, so feelings have often been established to some degree before a child’s first practice. Youth coaches, however, play an enormous role in whether or not that passion continues.

A child’s early exposure to sports and coaching often influences their desire to continue participating. Early coaching needs to be both positive and effective. Coaches need to balance making practices/games fun and improving athletically so the child develops feelings of self-efficacy associated with the sport. Few things are more motivating to children that the feeling of proficiency – when a child thinks he/she is good at a sport, they enjoy it more.

This can be a very delicate balancing act, and factors like stature, enjoyment and fundamental movement skills (FMS) play large roles in developing feelings of proficiency. Typically, athletes who have good FMS’s excel early on, and have greater early enjoyment of sports. Parents can greatly assist this process by working on FMS early in a child’s life and providing positive exposure to sport.

Coaches can recognize the importance of establishing passion by making sports enjoyable and productive. Possibly the most important goal of a youth sports coach should be to make each season so positive that the kids want to play another season. This keeps them in the “system” and allows them to progress.

Coaching

Having great coaches should be the first thing mentioned in any long term athlete development model. Unfortunately, it is not. Great coaches trump theoretical models every time and should be discussed before anything else in this process.

The approach used with each child may have more to do with long-term athletic success than any physical training method. Yes, the right training methods will elicit positive physiological responses, but the wrong coaching approach can make the athlete lose interest, confidence, and enjoyment of the sport.

Getting this wrong will render LTAD models useless, so having the right coach at the right time is essential to the process of athlete development. The right coach will be different at each stage of maturation and for each athlete, so there is no single solution.

The right approach, however, has the potential to increase self-efficacy and passion, and can establish positive traits such as work ethic, perseverance, coachability, and a healthy outlook toward sports. These positive traits and feelings may be the keys to sticking with a sport through tough training and the ups & downs associated with sports later in their development.

Great coaching should be used by both sport coaches and strength & conditioning professionals (SCP) alike. A SCP has the ability to balance out a poor coach and vice versa. Optimally, all coaches will be positive influences and contribute to the success of an athlete by teaching skills and making the process enjoyable enough to keep the passion burning.

The importance of having the “right coach at the right time” cannot be overstated in the development of an athlete. The right coach at 8 years old probably won’t be the right coach at 18, and the right coach for one athlete may not be the right coach for all athletes.

Typically, young athletes and parents don’t even know which coach is the right fit or if that person is even available. More often, we realize the negative experience when it’s too late and the damage has been done. For example, a young soccer player can be on a terrific path of development from age 8 to 14 until a poor coach absolutely ruins soccer for her. This can occur when athletes change clubs, move to a different age group, or have a coach who is simply a bad fit. This has the potential to make athletes lose passion/interest, decrease confidence or quit the sport altogether. Anyone who has been involved in sports for any length of time has seen this over and over again.

Coaches who value winning above development too early in an athlete’s career can stifle the developmental process and get athletes to focus on things that limit long-term success. These coaches often play favorites with young athletes and push certain athletes to excel (often their own child) while relegating others to less-important roles on the team. While this may work for some athletes, it can also have a negative effect on overall development. The “favorite” child may have false confidence in their early success and he/she may not learn how to work hard for that success. Other children may feel decreased confidence and end up quitting because the sport just isn’t fun anymore.

Unfortunately, high-quality coaches often feel compelled to work with older, more developed athletes because that’s what society deems as “better.” To be sure, some coaches are simply better-suited to work with older athletes, but a great youth coach has the potential to be one of the most influential figures in a child’s life. A year, early in life, with a bad coach could have easily derailed the careers of great athletes like Wayne Gretzky, Magic Johnson or Lionel Messi.

If we’re truly looking to develop great athletes through a long-term process, we must encourage great coaches to spend time with young athletes. This means that quality coaches may need to volunteer their time to work with young athletes, knowing that the payoff may not occur for many years.

It also means that SCP’s need to be aware of how each child is being coached and approach them with what they need. A child who has a negative sport coach may need a more positive approach from the SCP. Conversely, a talented child who has been coddled his whole life may need a hard-nosed influence to push him to be great.

Social/Environmental

It is impossible to ignore the fact that a child’s surroundings influence his/her sporting experiences, but this is also ignored by every LTAD model available. Spending time with friends is very important to most children. Sometimes, kids may be better off playing a sport with their friends than on a travel team comprised of kids who don’t know each other.

Geographic location will also influence long term athlete development. For example, a young child with a passion for lacrosse, but who lives in an

area with limited coaching/competition, will probably not have the opportunity to reach his potential like he would if he grew up in Maryland. A young gymnast may be identified as a potentially great diver in middle/high school. If she doesn’t like the coach or the other athletes on the diving team, she may never even give it a chance, and a potential Olympian may never try a sport. How many exceptional rugby players, fencers or team handball players have been born in America and were simply not exposed to these sports?

Access to quality experiences and identification of talent plays a huge role in the long-term success of an athlete.

Strength coaches may not have much control over this, but it’s certainly something we need to consider if the goal is to develop great athletes and achieve long-term success. Even if the goal is to create enjoyable experiences, the fact that opportunities are often limited should not be ignored.

An experienced coach may be able to suggest sports and/or coaches to families when talent is identified. While there is no guarantee that these suggestions will be acted upon, we should always think about what we can do rather than complain about a problem after the fact.

Parental Support

Parents have more of an influence than anyone in the process of long-term athlete development, and both sports coaches and SCP’s may need to step in to help guide them when appropriate. Some parents push too hard, while others expect too little. This is a delicate balancing act that must be considered as part of any long term plan.

Simply providing transportation to great coaching/training may be the difference needed to keep the flame burning in a young athlete. Conversely, negative conversations after a game may poison the well and create negative emotions related to a sport.

Simply providing transportation to great coaching/training may be the difference needed to keep the flame burning in a young athlete. Conversely, negative conversations after a game may poison the well and create negative emotions related to a sport.

Sports satisfaction surveys reveal that “having fun” is the main reason that most children like to participate in sports; however, the parents’ perception of why their children like to play sports is to “win.”

SCP’s and sport coaches can help create balance when support is not present. By making practice/training an enjoyable, positive experience, a child’s “emotional bank account” can be built up. Coaches may also need to have hard conversations with parents sometimes or at least talk to the athlete about how to communicate with the parent.

Coordination

With all of these factors in mind, it appears as though long term athlete development is much more complex than just the training methods used at different points in the maturation process or how many games to play each year. Of course, great training and sport coaching are necessary. That should be painfully obvious by now. But, besides great training and coaching, it also appears that many critical factors need to come together in a coordinated effort if we are truly looking for optimal development and great sporting experiences.

We have created “silos” that don’t have enough interaction with each other. Parents, sports coaches, and strength & conditioning specialists each have their silos where they do their work independently. This approach creates a lack of continuity for the young athlete. Sports coaches don’t know what kind of training is occurring outside of their practices. SCP’s have no input on the number or duration of practices, and parents often don’t know what’s best for their child, so they simply drop them off with a coach and hope he/she is doing the right thing.

Unfortunately, many adults seem to think that “their way” is the best approach, so there is little coordination between parents, coaches, and trainers.

It also goes without saying that the entire youth sports system is broken and has become more about the adults than the kids. Many books and articles have been written on this topic. Web sites have been created and Ted Talks were given. Even the US Olympic Committee is now supporting pediatric sports psychologists to help young athletes deal with the stresses of youth sports and to help parents and coaches deal with the challenges.

The problems are obvious, and rehashing them here seems pointless.

We are not going to fix this problem by complaining about it or attempting to tear it down.

In order to fix this broken system, a much more coordinated approach needs to be taken. Someone must intervene and change the system from the inside.

Most parents simply don’t know how to handle this overall development, so guidance is needed. Sport coaches usually have great knowledge of a sport, but lack knowledge in the area of complete athlete development. Many strength coaches are aware of the needs, but don’t have enough influence over the process, aren’t involved until later in an athlete’s career or simply want to stand on the outside and complain about it.

It is time for strength & conditioning professionals to step up and become coordinators of athletic development.

The SCP is armed with the knowledge to coordinate long term athlete development. It is up to this group to take a more active role in the education of parents and coaches. We need highly-qualified professionals who can effectively communicate and coordinate the “silos” in an effort to create positive experiences.

The SCP can teach coaches and parents how each aspect of athleticism is linked, and plans can be put in place to create well-rounded athletes.

This shift will require the SCP to get out of his/her comfort zone and think about athlete development as more than just lifting weights. The SCP will need to work within the structure of youth sports by educating parents and coaches, and taking their own egos out of the equation. We need to spend time teaching parents and coaches about fundamental motor skills, skill acquisition, strength and speed development, and all-around athletic development rather than specialization. With overuse injuries ranging from 37% to 68% depending on the sport, we can help reverse this trend.

This education will not put us out of jobs. On the contrary, educating coaches and parents about how to properly integrate strength & conditioning into a long term athlete development plan will secure our places in every organization. More coaches and parents will understand the need for training which will increase the demand for our specialized services. More trust will be placed in our hands because we will be viewed as allies rather than adversaries.

Without this coordination, the important people in this process will remain in their silos. But, a collective approach will yield far better results for everyone involved.

As you can see, long term athlete development cannot be distilled down to contrived models. The process is more complicated and many factors need to be addressed.

We have a great opportunity to influence a broken system from within, and make the changes that are needed for long term success. We need great coaches and coordinators to help develop athletes. It’s time to stop complaining and take action.

Jim Kielbaso is the President of the IYCA and Owner of Impact Sports Performance in Novi, MI. He is a former college strength & conditioning coach and the author of Ultimate Speed & Agility as well as dozens of articles published in various publications. Jim is also the father of three boys and has helped coach all of them in different sports, so long term athlete development is very important to him.

Jim Kielbaso is the President of the IYCA and Owner of Impact Sports Performance in Novi, MI. He is a former college strength & conditioning coach and the author of Ultimate Speed & Agility as well as dozens of articles published in various publications. Jim is also the father of three boys and has helped coach all of them in different sports, so long term athlete development is very important to him.

The old “windows of opportunity” Long Term Athlete Development model is a thing of the past. Learn the truth about LTAD and how to approach athletes at every level in the IYCA Certified Athletic Development Specialist, the gold-standard certification for anyone working with athletes 6-18 years old. The course materials were created by some of the most experienced and knowledgeable professionals in the industry, and the content is indisputably the most comprehensive of any certification related to athletic development. Learn more about the CADS certification here:

Beni is an IYCA Ambassador, Entrepreneur and CEO. He’s earned UEFA coaching badges and a BA in Physical Fitness & Sports Conditioning. He has professional experience across soccer, golf, and rugby, expanding programs in Texas and Ireland. He has founded GameLikeSoccerCoaching and BBsports Fitness and Nutrition.

Beni is an IYCA Ambassador, Entrepreneur and CEO. He’s earned UEFA coaching badges and a BA in Physical Fitness & Sports Conditioning. He has professional experience across soccer, golf, and rugby, expanding programs in Texas and Ireland. He has founded GameLikeSoccerCoaching and BBsports Fitness and Nutrition. There are different types of speed when it comes to training soccer athletes. In my last article I spoke about the

There are different types of speed when it comes to training soccer athletes. In my last article I spoke about the  Tactical Speed

Tactical Speed It is no secret that the development of the young athlete is multifaceted and it is the responsibility of the coach and/or trainer to take into consideration developmental, physical, and psychological aspects of training.

It is no secret that the development of the young athlete is multifaceted and it is the responsibility of the coach and/or trainer to take into consideration developmental, physical, and psychological aspects of training.  Coaches may recognize an exaggerated arch in the lower back, but that’s just one part of the equation. The ability to control anterior and posterior pelvic tilt is critical to sprinting, squatting, hinging, and a variety of athletic movements. Many athletes struggle with these movements because they simply don’t know how to create or control pelvic tilt.

Coaches may recognize an exaggerated arch in the lower back, but that’s just one part of the equation. The ability to control anterior and posterior pelvic tilt is critical to sprinting, squatting, hinging, and a variety of athletic movements. Many athletes struggle with these movements because they simply don’t know how to create or control pelvic tilt. Jim Kielbaso is the President of the IYCA and owner of

Jim Kielbaso is the President of the IYCA and owner of

Many high school and college-level athletes feel like they either need to get as big and strong as possible or they don’t value it at all. Some of that depends on the sport they play, and some depends on their environment or what their coaches value. We need to help athletes put strength/size into perspective, and teach them that these qualities should be developed as a PART of their overall development. In some cases, it’s a small part, and in other cases, it’s more important. But, concentrating ALL of your effort on lifting weights if usually not what athletes need.

Many high school and college-level athletes feel like they either need to get as big and strong as possible or they don’t value it at all. Some of that depends on the sport they play, and some depends on their environment or what their coaches value. We need to help athletes put strength/size into perspective, and teach them that these qualities should be developed as a PART of their overall development. In some cases, it’s a small part, and in other cases, it’s more important. But, concentrating ALL of your effort on lifting weights if usually not what athletes need.

On the other hand, if you had a session with fun games for athletes, like a game of tag, set up no limitations, and gave minimal coaching cues, their response was amped-up and their agility was faster than you could say undulating periodization. Not only that, but they were elated in their response and had unlimited energy to run around.

On the other hand, if you had a session with fun games for athletes, like a game of tag, set up no limitations, and gave minimal coaching cues, their response was amped-up and their agility was faster than you could say undulating periodization. Not only that, but they were elated in their response and had unlimited energy to run around. Erica Suter is a soccer performance coach at JDyer Strength and Conditioning in Baltimore, Maryland. She works with youth athletes across the state of Maryland in the areas of strength, conditioning, agility, and technical soccer training. Besides coaching, she is a passionate writer, and writes on youth fitness as well as soccer performance training on her blog

Erica Suter is a soccer performance coach at JDyer Strength and Conditioning in Baltimore, Maryland. She works with youth athletes across the state of Maryland in the areas of strength, conditioning, agility, and technical soccer training. Besides coaching, she is a passionate writer, and writes on youth fitness as well as soccer performance training on her blog  ever. Sport coaches, classroom teachers, and parents are now looking for specific solutions to the specific needs of niche populations within youth.

ever. Sport coaches, classroom teachers, and parents are now looking for specific solutions to the specific needs of niche populations within youth.  Fortunately, sports are not the “boys club” they once were. Sports participation amongst young women and girls is at an all-time high. Despite this increase, young women’s access to quality strength and conditioning programs is often limited compared to their young male counterparts. Due to an inaccurate cultural convention, misinformed coaches, and a variety of other factors, strength training has not traditionally been embraced as part of young female athlete culture.

Fortunately, sports are not the “boys club” they once were. Sports participation amongst young women and girls is at an all-time high. Despite this increase, young women’s access to quality strength and conditioning programs is often limited compared to their young male counterparts. Due to an inaccurate cultural convention, misinformed coaches, and a variety of other factors, strength training has not traditionally been embraced as part of young female athlete culture.  Additionally, homeschool parents are challenged with finding opportunities for their kids to socialize with other kids during school hours.

Additionally, homeschool parents are challenged with finding opportunities for their kids to socialize with other kids during school hours.

Instead, I’ll teach a drill and make sure athletes have good technique before moving forward. After they’ve gotten proficient in the drill, we’ll add some resistance. However, I don’t add so much resistance that it makes the movement look sloppy. My general rule is: The more sport-specific a drill, the lighter the resistance.

Instead, I’ll teach a drill and make sure athletes have good technique before moving forward. After they’ve gotten proficient in the drill, we’ll add some resistance. However, I don’t add so much resistance that it makes the movement look sloppy. My general rule is: The more sport-specific a drill, the lighter the resistance.

When developing athleticism, one question must be answered.

When developing athleticism, one question must be answered.  always ask is whether or not they are moving efficiently.

always ask is whether or not they are moving efficiently.  Paul Aanonson, MS, CSCS, FMS –

Paul Aanonson, MS, CSCS, FMS –

Jordan Tingman – CSCS*, USAW L1, ACE CPT, CFL1 is a graduate of Washington State University with a B.S. in Sports Science with a Minor in Strength and Conditioning. She completed internships with the strength & conditioning programs at both Washington State University and Ohio State University, and is currently a Graduate Assistant S & C Coach at Eastern Washington University.

Jordan Tingman – CSCS*, USAW L1, ACE CPT, CFL1 is a graduate of Washington State University with a B.S. in Sports Science with a Minor in Strength and Conditioning. She completed internships with the strength & conditioning programs at both Washington State University and Ohio State University, and is currently a Graduate Assistant S & C Coach at Eastern Washington University.

jumpers, weak legs just ain’t gonna cut it. It astonishes me how many coaches (sports or strength/performance) just don’t realize that.

jumpers, weak legs just ain’t gonna cut it. It astonishes me how many coaches (sports or strength/performance) just don’t realize that.  Bio:

Bio:

Doug Heslip is the owner of Heslip Elite Sports Performance Training in Negaunee, MI and the creator of Seek & Destroy – Elite Running Back Drills a video product for football coaches. He works with young athletes in a variety of sports and teaches football coaches how to incorporate speed & agility training into their sessions.

Doug Heslip is the owner of Heslip Elite Sports Performance Training in Negaunee, MI and the creator of Seek & Destroy – Elite Running Back Drills a video product for football coaches. He works with young athletes in a variety of sports and teaches football coaches how to incorporate speed & agility training into their sessions. Long term athlete development has been discussed for years, but the concept is still incredibly confusing for practitioners. Part of the reason for this confusion is that the models are missing details and coordination of efforts between coaches, trainers and parents.

Long term athlete development has been discussed for years, but the concept is still incredibly confusing for practitioners. Part of the reason for this confusion is that the models are missing details and coordination of efforts between coaches, trainers and parents.

identified some very important issues in many countries and sporting organizations, so he created a 3-stage model that emphasized long term athlete development over winning competitions. This premise challenged the approach of many coaches and got a lot of people to open their eyes to the problems in youth sports.

identified some very important issues in many countries and sporting organizations, so he created a 3-stage model that emphasized long term athlete development over winning competitions. This premise challenged the approach of many coaches and got a lot of people to open their eyes to the problems in youth sports.

While the theory of long term athlete development is well-intentioned, the models have yet to produce exceptional athletes in real life. In fact, even the researchers admit that there was no real data to support any of the models. In a great review of some of the relevant literature, Guy Razi and Kieran Foy showed that the data does not support these models. It was all a great idea, but these models were nothing more than theoretical. To this day, no athlete has gone through the entire model the way it was originally laid out, and achieved a high level of success.

While the theory of long term athlete development is well-intentioned, the models have yet to produce exceptional athletes in real life. In fact, even the researchers admit that there was no real data to support any of the models. In a great review of some of the relevant literature, Guy Razi and Kieran Foy showed that the data does not support these models. It was all a great idea, but these models were nothing more than theoretical. To this day, no athlete has gone through the entire model the way it was originally laid out, and achieved a high level of success.

Without passion, the entire LTAD model comes to a grinding halt, so this cannot be ignored.

Without passion, the entire LTAD model comes to a grinding halt, so this cannot be ignored.

Simply providing transportation to great coaching/training may be the difference needed to keep the flame burning in a young athlete. Conversely, negative conversations after a game may poison the well and create negative emotions related to a sport.

Simply providing transportation to great coaching/training may be the difference needed to keep the flame burning in a young athlete. Conversely, negative conversations after a game may poison the well and create negative emotions related to a sport.

Jim Kielbaso is the President of the IYCA and Owner of

Jim Kielbaso is the President of the IYCA and Owner of