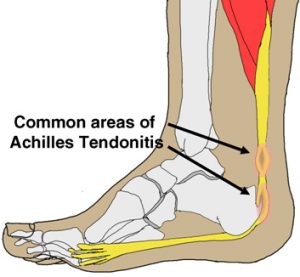

When working in an outpatient orthopedic rehab or sports performance facility you will commonly be treating Achilles Tendon injuries.

That could be an Achilles Tendon Rupture, Achilles Tendinitis, or Achilles Tendinopathy. All are slightly different in their mechanism of injuries but all have the same milestones and goals to progress through in order to experience a full recovery. Obviously a rupture will take a longer time frame to recover than a tendinitis or tendinopathy scenario (but that’s probably a topic for a completely separate post).

***Be sure to pay special attention to step #3 as this is often missed by many rehab clinicians and strength coaches

The first step into the process is understanding the influence of pain on the problem as well as anatomy and biomechanics influence on the problem. These are two separate issues, as often pain does not correlate directly with the amount of tissue damage present. This makes it important to understand the guidelines of pain (what is okay to work through and what is not okay to exercise through).

We discuss this in the below video:

The other important consideration we pointed out in the video above is the anatomy of the calcaneus. The shape of the heel creates a compression force on the Achilles tendon when stretched which is important to consider if the pain or location of the injury is at the base of the tendon or if the tendon is highly sensitive. For these reasons, it is often NOT a good idea to stretch your Achilles tendon (especially when you are experiencing pain).

Once you understand the pain and irritating factors it is important to understand how to re-establish capacity back into the tendon without aggravating the tissue.

We do this through strengthening in a NON stretched position FIRST. Then start gradually working our way back into STRENGTHENING THROUGH a stretched position. Not hanging out for 30 seconds in a sustained stretched position.

In Part 2: the video below we discuss our two favorite exercises to start accomplishing this:

Step #1 and #2 are the easy parts of the rehab gameplan. However, this will probably only solve about 70% of cases. In the other 30% of cases, you need to consider other factors that may be influencing pain, as well as return to play scenarios for those involved with higher levels of activity!

To understand this further we need to consider the two main archetypes of feet you will see…

A pronated (flat) foot, and a supinated (high arch) foot.

Depending on what media and other healthcare providers have led you to believe, you probably feel that both flat feet and arched feet are undesirable. However, that couldn’t be further from the truth!

Both types of feet are necessary for everyday tasks. It’s no different than the ability to rotate your head right and left. Flat feet and arched feet are two extremes that the body should be capable of experiencing both. If the foot is not adaptable at creating both, and experiencing both at the correct moment, then you limit the foot’s capabilities.

During gait or walking our foot SHOULD experience supination, to pronation, to re-supination. That is normal and necessary mechanics of walking, gait, running, etc.

Pronation is needed to absorb force (store potential energy) or absorb/attenuate forces. Supination is necessary to produce force by creating a rigid foot.

The body’s ability to re-supinate the foot is accomplished through the windlass mechanism. Which is only created by getting great toe extension. The only way to get great toe extension during gait is by allowing the foot to pronate and weight bear over the great toe as your center of mass moves forward (horizontally) during gait, walking, running, etc.

If you cannot pronate effectively, you will not create an effective windlass mechanism and thus not experience re-supination. So all those towel scrunches or tripod foot exercises you are doing with the knee straight have little carry-over to life as during walking, running, etc we are moving forward! The tibia is moving forward, the knee is moving forward, the hips and body are moving forward…

So we must pronate effectively to allow our body, knee, and tibia to move forward. Load the foot and the kinetic chain. Experience pronation effectively and let the body get over the great toe to effectively utilize the windlass mechanism to re-supinate the foot and prepare for propulsion. The video below will hopefully give you a better understanding:

This above step #3 is often the most overlooked problem to Achilles injuries as well as many foot/ankle/knee problems. Understand it, and you can make a world of difference for people who seem to be constantly stuck in a state of injury or rehab purgatory.

Finally, the last step in the process is exposing the tendon back to a situation similar to sport.

Sure eccentric loading is great for the tendon histology development, and the athlete will certainly experience eccentric loading of the tendon in sport. However, a concept often overlooked is the ability to create co-contraction of the kinetic chain to distribute or absorb force more effectively. When running or jumping, the body needs relative stiffness in the ankle (as well as all the other joints) to not crumble when applying a force into the ground. Then store the potential energy to propel themselves forward. Look at any sprinter at top-end speed or dunker taking off from a one-foot jump approach.

Those who do it effectively create a lot of stiffness around their joints at ground contact. Meaning you will not see a large counter movement occur during a one-foot jump approach (or really even someone who is more of an elastic two-foot jumper). A sprinter you will notice a very stiff an rigid foot and even knee at ground contact. This is because the body is co-contracting the calf, hamstring, quad, and glute to quickly apply force and absorb force through the kinetic chain.

In video 4 we discuss some of my favorite dynamic exercises that take into account teaching co-contraction at ground contact.

If you found this article helpful, you will probably love the newly revamped Youth Athletic Assessment Specialist 2.0 course that I helped create for the IYCA. I hope this gives you a better understanding of the Achilles tendon and how to address it in your training programs.

Dr. Greg Schaible is a physical therapist and strength coach specializing in athletic performance and a regular contributor the the IYCA. Greg is the owner of On Track Physiotherapy and owner of the popular online education resource Sports Rehab Expert. Greg works with athletes and active individuals of all ages. As a former athlete himself, he attended The University of Findlay and competed in both Indoor and Outdoor Track & Field where he earned honors as a 5x Division II All-American and a 6x Division II Academic All-American.

Dr. Schaible was instrumental in putting together the completely updated version of the Youth Athletic Assessment Specialist 2.0 course that covers a wide range of screens, performance assessments, and advanced assessment techniques. Learn more about the YAAS 2.0 by clicking the image below.

Jordan Tingman – CSCS*, USAW L1, ACE CPT, CFL1 is a graduate of Washington State University with a B.S. in Sports Science with a Minor in Strength and Conditioning. She completed internships with the strength & conditioning programs at both Washington State University and Ohio State University, and is currently a Graduate Assistant S & C Coach at

Jordan Tingman – CSCS*, USAW L1, ACE CPT, CFL1 is a graduate of Washington State University with a B.S. in Sports Science with a Minor in Strength and Conditioning. She completed internships with the strength & conditioning programs at both Washington State University and Ohio State University, and is currently a Graduate Assistant S & C Coach at

of strength and conditioning on social media. You’ll be much more inclined to find strength coaches showcasing impressive feats of strength, power, speed or even balance. How often do you see coaches talking about amazing flexibility routines?

of strength and conditioning on social media. You’ll be much more inclined to find strength coaches showcasing impressive feats of strength, power, speed or even balance. How often do you see coaches talking about amazing flexibility routines?

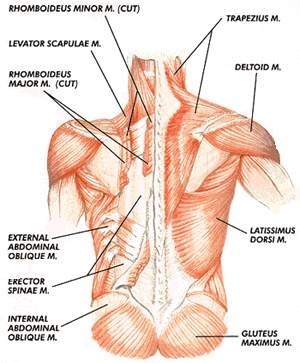

It is very common for athletes to experience lower back pain, especially when they begin a new training program or train harder than they have in the past. As muscles get sore and/or stiff from training, they will “hold onto” certain positions as a way to maintain different positions. Often, tightness in the internal hip/back muscles throws postural alignment off, which can lead to even more pain. This pain can be felt in various parts of the spine, but in this article, I will mostly focus on stretching muscle groups in the hips and lower back.

It is very common for athletes to experience lower back pain, especially when they begin a new training program or train harder than they have in the past. As muscles get sore and/or stiff from training, they will “hold onto” certain positions as a way to maintain different positions. Often, tightness in the internal hip/back muscles throws postural alignment off, which can lead to even more pain. This pain can be felt in various parts of the spine, but in this article, I will mostly focus on stretching muscle groups in the hips and lower back.