Olympic-style weightlifting exercises have found their place in the process of developing athletes, a process that often begins during childhood and early adolescence. Their exact role, however, is still controversial. While the Olympic-style weightlifting exercises have found their place in the training of elite athletes, the best way to utilize them with youth and adolescence athletes is still unclear.

found their place in the training of elite athletes, the best way to utilize them with youth and adolescence athletes is still unclear.

At its core, strength training essentially gives an upgrade to basic motor patterns like squatting, hinging and pressing but also lunging, pulling and pushing, and this increase in muscular strength is an important part of the development of a young athlete. Long term athlete development (LTAD), however, is more than just making young athletes stronger. It is a multidisciplinary approach aimed to improve skills and physical attributes that are necessary to compete in sport. It is a learning process that moves from the foundation of athleticism to the acquisition of sport-specific skills.

Olympic weightlifting is similar. It requires a great deal of time to develop the skills and physical attributes necessary for athletes to excel in the snatch, clean and jerk. Many weightlifting experts such as Harvey Newton and Bob Takano have written and spoken about how much time and energy is required to develop great weightlifters.

The 10,000 hour rule has often been referenced in respect to developing great weightlifters. As far back as 1952, Soviet weightlifting expert Madvedyev wrote about the need for 10,000 hours of training in the long term development plan for weightlifters. Takano, who has trained athletes – including many top American weightlifters – for over 30 years, has said that it takes 10,000 repetitions to develop proficiency in weightlifting.

To make this happen, it would take about five years of training and competing in weightlifting, at an average of 2000 repetitions a year to become proficient in the snatch, clean and jerk. This comes out to approximately 40 repetitions a week divided between the three major lifts and their derivatives. With the average number of lifting sessions per week being only two (2) for high school athletes and younger, 20 reps a day would need to be performed. If there was a focus on quality & intensity, 20 repetitions would make up almost 50% of the total average training volume for a single training session of approximately 60 minutes, which will typically also include speed, agility and accessory strength training.

To make this happen, it would take about five years of training and competing in weightlifting, at an average of 2000 repetitions a year to become proficient in the snatch, clean and jerk. This comes out to approximately 40 repetitions a week divided between the three major lifts and their derivatives. With the average number of lifting sessions per week being only two (2) for high school athletes and younger, 20 reps a day would need to be performed. If there was a focus on quality & intensity, 20 repetitions would make up almost 50% of the total average training volume for a single training session of approximately 60 minutes, which will typically also include speed, agility and accessory strength training.

Athletes would have to start this kind of training program in 8th grade and continue, year-round until graduation to get the requisite number of repetitions to be proficient in the eyes of the experts cited above. This is a tremendous amount of time and effort that most coaches, athletes or parents would never commit to.

Still, many coaches prescribe Olympic weightlifting to young athletes in an effort to harness the power development benefits of the exercises, not worrying about proficiency. Many coaches spend less than a week teaching the lifts before loading them and testing athletes. If they’re lucky, young athletes will be taught the lifts through a progression that might take several weeks.

This is a stark contrast to the way master-level coaches like Takano and Madvedyev suggest.

Both Faigenbaum (2009) and Molina (2006) have warned coaches about this thought process. They have explained that, if an athlete does not have the necessary amount of time to gain proficiency in the snatch, clean and jerk, the risks associated with the exercises far exceed the benefits.

But, what if there was a way to teach young athletes how to perform Olympic-style weightlifting exercises as they learn how to squat, jump and throw or perform any of the fundamental motor skills needed to compete in sport? Or take advantage of the benefits of OLY lifting without going through the arduous process of performing 10,000 repetitions?

Most adolescent athletes are still in the process of learning and mastering a broad variety of skills that represent the foundation of athleticism. Making a teenage athlete stronger is certainly valuable, but strength training is usually not the primary goal for most athletes in a long term athlete development (LTAD) model. LTAD is not about training high school and collegiate athletes as they were weightlifters: it is about teaching them the proper skills/form to be able to benefit from a broad variety of movements that can, and will, improve performance on the field of play if properly executed in training.

It is rather intuitive, therefore, that time is a major limiting factor that can somehow compromise the ability to learn how snatch,  clean and jerk.

clean and jerk.

When it comes to developing a more explosive triple-extension (a skill that will be beneficial in a variety of sports), studies have shown that weighted pulls (Olympic-style pulls and high pulls from the ground and/or from the power position) can display similar, if not superior, results compared to the full snatch, clean and jerk. Because the technique requirements are so much lower when performing pulls (compared to the full version of each lift), they can be implemented into a program much quicker than the full lifts. Eliminating the catching phase of each lift also makes them much safer for inexperienced lifters.

When an inexperienced lifter is working with relatively low weights due to lack of technical skill, he/she will not derive the same benefit from the exercise compared to performing heavy Olympic-style weightlifting exercises. The main benefit at this point is learning technique as he/she practices. For an athlete who is not competing in the sport of weightlifting, this could be considered a waste of time.

On the other hand, pulling a bar from the power position into a shrug – the most basic variation of the weightlifting pull, called “extension” or simply “pull” – can be performed almost immediately by most athletes.

Recent studies have shown that peak power output does not really differ much from the full execution of the snatch, clean and jerk and the “partial” execution of a pull or an high pull. In fact, most studies are showing that peak power output is actually greater in the mid-thigh clean pull and/or power shrug compared to the full movements. This means that athletes can learn how to be explosive and develop a stronger and more powerful musculature of the lower extremity simply by adding pulls and high pulls in their training instead of being required to spend the time to develop proficiency in the complete lifts.

Recent studies have shown that peak power output does not really differ much from the full execution of the snatch, clean and jerk and the “partial” execution of a pull or an high pull. In fact, most studies are showing that peak power output is actually greater in the mid-thigh clean pull and/or power shrug compared to the full movements. This means that athletes can learn how to be explosive and develop a stronger and more powerful musculature of the lower extremity simply by adding pulls and high pulls in their training instead of being required to spend the time to develop proficiency in the complete lifts.

Can they still learn how to snatch, clean and jerk? Absolutely. If they have the time, these are great exercise to learn and they can surely add some value to the training of young athletes. But, when time is limited, implementing a pulling variation is an excellent way to derive the benefits of Olympic lifting movements without forcing non-weightlifting athletes to spend the time to master the lifts.

Besides the performance benefits, another reason to teach pulls to young athletes involves a motor learning component. Athletes seem to learn complex movement patterns by transferring skills from task to task. This is the essence of the “transfer of learning theory” which states that the learning of complex skills – such as sport-specific skills – relies on what psychologists have named the transfer-appropriate processing (TAP) approach. This theory explains how complex, highly organized skills can be learned by adapting neurological patterns (i.e.inter- and intra-muscular coordination, timing, rate of force development and peak power output) previously learned to accomplish a new task.

This is more than just changing the superficial parameters on a set motor scheme as Schmidt originally suggested. Instead, it appears that a brand new motor pattern can be created from scratch by transferring over skills previously learned in a different context. For instance, if an athlete already knows how to perform a kip (a fundamental skill in gymnastics), he or she will be more likely to learn how to pole vault – one of the most advanced, complicated skills in track and field – in a much more efficient way than an athlete who does not understand how to “pull him/herself into the bar.” Similarly, if an athlete already knows how to jump, he or she will more easily learn how to perform a weighted pull from mid-thigh. Once an athlete is familiar with a weighted pull, it will be easier for him/her to learn how to complete a full Olympic-weightlifting movement in the future. So, the ability to forcefully extend the lower extremities, and transfer force from the lower body to the upper body, will be better able to transfer those skills to other movements such as a clean, snatch, tackle or throw.

Weighted pulls sit on a relatively low level along the motor learning continuum described by Antoinette Gentile in 1972. Pulls and high pulls have a relatively low level of complexity and inter-trial variability – they are just “above” jumping skills in a theoretical hierarchy, but far below snatching, cleaning and jerking which represent a very high level of complexity and variability.

The learning process that takes place between being able to jump to learning how to pull, therefore, is much shorter than the one that takes place between being able to pull to learning how to snatch, clean and/or jerk. Anyone who has experience teaching these skills knows this to be true. But, trying to go from a jump to a full Olympic movement is very difficult. The intermediate step of teaching the pull is not only a great way to bridge that learning gap, it also give you a training tool that can derive immediate results.

As you can see, teaching and implementing Olympic lifting pulling variations with young athletes can have both training and motor learning benefits. We know that young athletes benefit from the development of both strength and coordination, so it seems logical to utilize these movements as part of a long term approach.

Antonio Squillante is the Director of Sports Performance at Velocity Sports Performance in Los Angeles, California. He is in charge of the youth development program which include over 100 athletes 17 years old and under competing in many different sports. Antonio graduated summa cum laude from the University San Raffaele – Rome, Italy – with a Doctorate Degree in Exercise Science. He has worked in college and professional athletics, has written numerous articles and holds certifications from multiple organizations.

Antonio Squillante is the Director of Sports Performance at Velocity Sports Performance in Los Angeles, California. He is in charge of the youth development program which include over 100 athletes 17 years old and under competing in many different sports. Antonio graduated summa cum laude from the University San Raffaele – Rome, Italy – with a Doctorate Degree in Exercise Science. He has worked in college and professional athletics, has written numerous articles and holds certifications from multiple organizations.

The IYCA Youth Fitness Specialist certification is the industry gold-standard for youth fitness and sports performance. Click on the image below to learn more about the YFS1 certification program.

Pause Bench Press Progression – In the last installment of this article series, we talked about the importance of exercise progressions and the front squat progression we utilize with our middle school and high school athletes. It can be found at

Pause Bench Press Progression – In the last installment of this article series, we talked about the importance of exercise progressions and the front squat progression we utilize with our middle school and high school athletes. It can be found at

where the barbell will be placed on the deltoids near the upper clavicle. To address this, our teaching progression includes the “free weight squat,” something I stole from Iowa’s Football Strength & Conditioning Coach, Chris Doyle. The free weight squat is basically a front squat with the arms pointed straight ahead instead of gripping the bar. This teaches athletes the proper barbell placement when performing the front squat.

where the barbell will be placed on the deltoids near the upper clavicle. To address this, our teaching progression includes the “free weight squat,” something I stole from Iowa’s Football Strength & Conditioning Coach, Chris Doyle. The free weight squat is basically a front squat with the arms pointed straight ahead instead of gripping the bar. This teaches athletes the proper barbell placement when performing the front squat. bell should swing up to shoulder level, while keeping the arms straight. A common mistake is the bending of the elbows which engages the upper body. This is something we want to avoid. The bending of the elbows also takes emphasis away from the hips. We typically use the double arm swing, but you can also utilize a single arm version of the exercise. When performing the single arm exercise the one additional coaching cue is that we turn the thumb backwards when the bell goes in between the legs. The snap of the hips and minimal arm use is the exact same as the double arm version of the KB Swing.

bell should swing up to shoulder level, while keeping the arms straight. A common mistake is the bending of the elbows which engages the upper body. This is something we want to avoid. The bending of the elbows also takes emphasis away from the hips. We typically use the double arm swing, but you can also utilize a single arm version of the exercise. When performing the single arm exercise the one additional coaching cue is that we turn the thumb backwards when the bell goes in between the legs. The snap of the hips and minimal arm use is the exact same as the double arm version of the KB Swing. programs, how do you choose the right one?

programs, how do you choose the right one? Between 12-14 years old, you might see a more intense sports performance program but the underlying culture should remain the same. There should always be a positive environment with coaches who serve as role models. Athletes should feel good about what they’re doing and praised for their effort.

Between 12-14 years old, you might see a more intense sports performance program but the underlying culture should remain the same. There should always be a positive environment with coaches who serve as role models. Athletes should feel good about what they’re doing and praised for their effort.

At a minimum, a good sports performance program should be very safe and organized. Sure, accidents happen, but a young athlete’s health is top priority, so they should never be engaged in anything dangerous.

At a minimum, a good sports performance program should be very safe and organized. Sure, accidents happen, but a young athlete’s health is top priority, so they should never be engaged in anything dangerous.

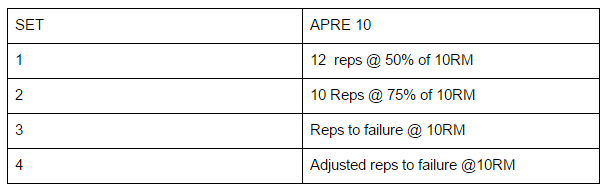

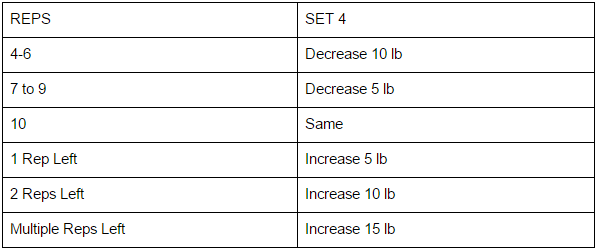

After the warm-up, the strength training program should be completed in a systematic order. As stated previously, this order of exercise should increase performance as well as prevent any training induced injury. The first exercise performed should be the one that requires the highest degree of technical proficiency and/or speed of movement. If you incorporate Olympic movements into your program or have traditional barbell exercises performed at a high rate of speed, the beginning of the training session is the appropriate place for these exercises. The Strength & Conditioning Professional (SCP) should have the athlete complete a few warm-up sets, gradually increasing load until he or she is ready to complete the first working set.

After the warm-up, the strength training program should be completed in a systematic order. As stated previously, this order of exercise should increase performance as well as prevent any training induced injury. The first exercise performed should be the one that requires the highest degree of technical proficiency and/or speed of movement. If you incorporate Olympic movements into your program or have traditional barbell exercises performed at a high rate of speed, the beginning of the training session is the appropriate place for these exercises. The Strength & Conditioning Professional (SCP) should have the athlete complete a few warm-up sets, gradually increasing load until he or she is ready to complete the first working set.

Mark Naylor is an Assistant Strength & Conditioning Coach for the Arizona Cardinals and a contributor to the IYCA book Principles of Athletic Strength & Conditioning. Before joining the Cardinals, Mark was the Head S & C Coach at Eastern Kentucky and an Assistant S & C Coach with University of Michigan Football Program. He previously served as the Director of Ball State University’s football strength & conditioning program and has also spent time with the Baltimore Ravens and at Missouri Southern. He earned his BS from Missouri Southern and his MS from Ball State University.

Mark Naylor is an Assistant Strength & Conditioning Coach for the Arizona Cardinals and a contributor to the IYCA book Principles of Athletic Strength & Conditioning. Before joining the Cardinals, Mark was the Head S & C Coach at Eastern Kentucky and an Assistant S & C Coach with University of Michigan Football Program. He previously served as the Director of Ball State University’s football strength & conditioning program and has also spent time with the Baltimore Ravens and at Missouri Southern. He earned his BS from Missouri Southern and his MS from Ball State University. affected negatively due to the load being too heavy for the athlete to complete a full range of motion. This is where we see half squats, rounded backs on deadlifts, barbells stapling athlete’s chests on the bench press, cleans being pulled in atrociously inefficient manners, etc. The list goes on and on. The implications are numerous and can prove to be quite detrimental for the athlete.

affected negatively due to the load being too heavy for the athlete to complete a full range of motion. This is where we see half squats, rounded backs on deadlifts, barbells stapling athlete’s chests on the bench press, cleans being pulled in atrociously inefficient manners, etc. The list goes on and on. The implications are numerous and can prove to be quite detrimental for the athlete. Smart coaches understand games aren’t won with deceptive bench press numbers, but rather with healthy athletes who are able to play to the best of their ability. At certain levels, the strength coach is around their athletes more often than their position or head coaches. Actions and messages portrayed by the strength coach can often resonate with athletes. Pushing these false standards of success can send out the message that it’s okay to cut corners. Keep the lessons and messages honest. After all, one of the best privileges of being a coach of any kind is seeing an athlete grow to become an honorable human being, not just a standout on the playing field.

Smart coaches understand games aren’t won with deceptive bench press numbers, but rather with healthy athletes who are able to play to the best of their ability. At certain levels, the strength coach is around their athletes more often than their position or head coaches. Actions and messages portrayed by the strength coach can often resonate with athletes. Pushing these false standards of success can send out the message that it’s okay to cut corners. Keep the lessons and messages honest. After all, one of the best privileges of being a coach of any kind is seeing an athlete grow to become an honorable human being, not just a standout on the playing field. Joe Powell is an Assistant Strength & Conditioning Coach and Adjust Faculty Member at Central Michigan University. He has experience in a variety of settings including Division I Athletics, private sports performance, high school S & C, personal training and teaching college courses.

Joe Powell is an Assistant Strength & Conditioning Coach and Adjust Faculty Member at Central Michigan University. He has experience in a variety of settings including Division I Athletics, private sports performance, high school S & C, personal training and teaching college courses.

Joshua Ortegon is co-founder and the Director of Sports Performance Enhancement at Athlete’s Arena in Irmo, SC. Joshua earned his Bachelor of Science degree in Exercise Science from Western Michigan University in 2000.

Joshua Ortegon is co-founder and the Director of Sports Performance Enhancement at Athlete’s Arena in Irmo, SC. Joshua earned his Bachelor of Science degree in Exercise Science from Western Michigan University in 2000.

Julie is the Executive Director of the International Youth Conditioning Association (IYCA). She grew up as an athlete and played collegiate softball at Juniata College. She currently owns and operates her own youth fitness business pouring into young athletes. Her areas of expertise are youth sport performance, youth fitness business and softball training/instruction. Julie grew up on a dairy farm and can challenge the best of the best in a cow-milking contest. 😉

Julie is the Executive Director of the International Youth Conditioning Association (IYCA). She grew up as an athlete and played collegiate softball at Juniata College. She currently owns and operates her own youth fitness business pouring into young athletes. Her areas of expertise are youth sport performance, youth fitness business and softball training/instruction. Julie grew up on a dairy farm and can challenge the best of the best in a cow-milking contest. 😉