As our NFL Combine Training program gets started, it is always exciting for me to get to know and help a group of talented, motivated athletes. It’s also a time that makes me examine athlete development in a different way.

Most coaches discuss athlete development in terms of working with young athletes in an effort to help them prepare for the future. With these guys, I get to look at the process backward and evaluate what they may have missed at some point in their development. So, it’s amazing to see these guys in the morning, watch 8-year-olds in the evening, and think about everything that happens in the years between.

Through the years, I’ve seen some interesting trends, and the training we do with the older guys always helps us train younger athletes more effectively because we have a chance to “look into the crystal ball” a little and see what they will need as they get older.

Sometimes you’ll hear coaches say things like “If he had used my methods, he would have been so much better.” I don’t look at it like this at all. So many things go into athlete development, that we don’t know exactly what would have happened if their training was different.

So, without judgment, I simply notice some trends in these guys that help me do a better job with younger athletes in an effort to clear up some issues before they are a problem down the road. While many of these guys will play professional sports, their development isn’t always as pretty as you’d expect.

Four things that I have noticed are:

- Misunderstanding of strength & size

- Lack of attention to movement quality

- Lack of attention to flexibility/mobility

- Under-appreciation for recovery

What’s interesting about this is the fact that we, as coaches, can help younger athletes avoid these errors before they become a problem. Let me briefly address each area so you understand what I’m thinking:

Misunderstanding of strength & size

Many high school and college-level athletes feel like they either need to get as big and strong as possible or they don’t value it at all. Some of that depends on the sport they play, and some depends on their environment or what their coaches value. We need to help athletes put strength/size into perspective, and teach them that these qualities should be developed as a PART of their overall development. In some cases, it’s a small part, and in other cases, it’s more important. But, concentrating ALL of your effort on lifting weights if usually not what athletes need.

Many high school and college-level athletes feel like they either need to get as big and strong as possible or they don’t value it at all. Some of that depends on the sport they play, and some depends on their environment or what their coaches value. We need to help athletes put strength/size into perspective, and teach them that these qualities should be developed as a PART of their overall development. In some cases, it’s a small part, and in other cases, it’s more important. But, concentrating ALL of your effort on lifting weights if usually not what athletes need.

Don’t get me wrong, MANY athletes lack strength, so they need to make this priority. But, many others simply don’t understand how strength training fits into a comprehensive athlete development program, and it’s our job to teach them.

Lack of attention to movement quality

I’m always surprised at how few elite level athletes have gotten much coaching on the way they move. They often haven’t been taught footwork, running technique, or posture, and it’s incredibly rare to meet an athlete who has been coached on their overall quality of movement.

We spend a ton of time teaching acceleration and sprinting mechanics as we work on the 40-yard dash. In many cases, this is the first time they’ve ever gotten this kind of in-depth instruction.

We also give them feedback on the way they look when they move because scouts want to see fluid athletes who can move through space effortlessly. This is about footwork, posture, and the subjective qualities that make them appear to be more or less athletic. I’m talking about things like taking too many choppy steps, heavy feet, rounded backs, flailing arms, or robotic movements. These qualities need to be taught at an early age so athletes feel more natural moving this way. Trying to teach 23-year-olds how to change this in six weeks is not ideal.

This always makes me realize how important it is for us to teach kids these things when they’re younger, and I hope you do the same.

Lack of attention to flexibility/mobility

College coaches tell me all the time that their athletes come in stiff, and they wish there was more of a focus on flexibility/mobility in high school. Then, I hear high school coaches talk about how tight their kids are, and they wish they would have done something about it earlier.

I see the same thing when training guys for the NFL – a lot of athletes simply don’t give enough attention to this.

So, we need to recognize this pattern and make sure we spend enough time keeping athletes mobile and supple. That doesn’t mean we need to turn kids into contortionists, but flexibility/mobility should be a part of every program. Whether that comes in the form of quality strength training, movement training, or direct flexibility/mobility work is up to you, but make this a priority before it’s a problem that affects everything they do.

Under-appreciation for recovery

Athletes often think that more is better and they believe that they can handle much higher volumes than they should. They rarely take recovery seriously. Instead, they have poor diets and severely lack sleep. The combination of high-volume training and poor recovery is a recipe for disaster.

Sometimes that disaster is obvious and athletes get sick or hurt. More often, it’s discreet and manifests itself as a lack of progress. Athletes train, train, train, but never get the results they desire because they simply don’t understand that recovery is the key to progress.

Athletes usually think that the stimulus (i.e. training) is where are of the gains take place. They don’t realize that the stimulus is simply a way to get their bodies to adapt and improve during recovery. Without adequate recovery, the stimulus won’t elicit great results.

We need to teach athletes the value of recovery, and how to schedule their training to maximize the results. We also need to teach them that all activity dips into their recovery, so their practice schedule, individual skill lessons, physical education classes, and performance training all need to be considered together not by themselves.

I hear athletes say it all the time – “I’m OK. I can do more.”

Yes, I know you CAN do more, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to be helpful. Trust me, I’d rather have an athlete want to do more than one who doesn’t do anything, but motivated athletes just keep doing more until there is a problem. We can teach them the value of appropriate scheduling and how to maximize their recovery.

There are many things that go into athlete development, so I find it fascinating to examine the process from the top down just as much as from the bottom, up. We will always need to give young athletes variety, teach them a love for moving, and give them quality training at the right times throughout their development. Hopefully, understanding these trends will help you create programs that allow athletes to avoid these issues and become the best versions of themselves as they develop.

Jim Kielbaso

Jim Kielbaso is the President of the IYCA and owner of

Impact Sports Performance in Novi, Michigan. He has authored multiple books, articles and training products and has spoken at events around the world. He holds a BS in Exercise Science, an MS in Kinesiology and has gone through multiple certifications through the IYCA, NSCA, NASM and more. Jim is a former college strength & conditioning coach and has trained thousands of athletes at every level of competition. He runs a successful

NFL Combine training program in Michigan and has been hired as a consultant for major sports programs like the University of Michigan Football Program and the University of Kentucky Basketball Program.

The IYCA Certified Athletic Development Specialist is the gold-standard certification for anyone working with athletes 6-18 years old. The course materials were created by some of the most experienced and knowledgeable professionals in the industry, and the content is indisputably the most comprehensive of any certification related to athletic development. Learn more about the CADS certification here:

It is no secret that the development of the young athlete is multifaceted and it is the responsibility of the coach and/or trainer to take into consideration developmental, physical, and psychological aspects of training.

It is no secret that the development of the young athlete is multifaceted and it is the responsibility of the coach and/or trainer to take into consideration developmental, physical, and psychological aspects of training.

Brett Bartholomew is a strength and conditioning coach, author, consultant, and Founder of Art of Coaching™. His experience includes working with athletes both in the team environment and private sector along with members of the United States Special Forces and members of Fortune 500 companies.

Brett Bartholomew is a strength and conditioning coach, author, consultant, and Founder of Art of Coaching™. His experience includes working with athletes both in the team environment and private sector along with members of the United States Special Forces and members of Fortune 500 companies.

t of questions about how to get your foot in the door or how to become a high school strength and conditioning coach. I also happen to work in several high schools, I post a lot of content from weight rooms, and I love working in high school strength and conditioning, so it makes sense that people ask those questions. But, is this job really right for you?

t of questions about how to get your foot in the door or how to become a high school strength and conditioning coach. I also happen to work in several high schools, I post a lot of content from weight rooms, and I love working in high school strength and conditioning, so it makes sense that people ask those questions. But, is this job really right for you? Jim Kielbaso is the President of the IYCA and Owner of

Jim Kielbaso is the President of the IYCA and Owner of

3. Calisthenics: The simple stuff like we did back in P. E. Remember jumping jacks? How about the lost art of jumping rope? Calisthenics are a fantastic tool for warming up and coordination activities. Simple? Yes… but much more effective than jogging around a soccer field if the goal is to improve athleticism.

3. Calisthenics: The simple stuff like we did back in P. E. Remember jumping jacks? How about the lost art of jumping rope? Calisthenics are a fantastic tool for warming up and coordination activities. Simple? Yes… but much more effective than jogging around a soccer field if the goal is to improve athleticism.

Jeremy Frisch is the owner and director of

Jeremy Frisch is the owner and director of

Jordan Tingman – CSCS*, USAW L1, ACE CPT, CFL1 is a graduate of Washington State University with a B.S. in Sports Science with a Minor in Strength and Conditioning. She completed internships with the strength & conditioning programs at both Washington State University and Ohio State University, a Graduate Assistant S & C Coach at

Jordan Tingman – CSCS*, USAW L1, ACE CPT, CFL1 is a graduate of Washington State University with a B.S. in Sports Science with a Minor in Strength and Conditioning. She completed internships with the strength & conditioning programs at both Washington State University and Ohio State University, a Graduate Assistant S & C Coach at

Brett Klika is a youth performance expert and a regular contributor to the IYCA who is passionate about coaching young athletes. He is the creator of the

Brett Klika is a youth performance expert and a regular contributor to the IYCA who is passionate about coaching young athletes. He is the creator of the  can be done anywhere. Many coaches also look for ways to help athletes get better at push ups, but simply doing them more often isn’t a great way for many people to improve, especially those who aren’t capable of performing many good push ups.

can be done anywhere. Many coaches also look for ways to help athletes get better at push ups, but simply doing them more often isn’t a great way for many people to improve, especially those who aren’t capable of performing many good push ups. way we consume information about strength and conditioning, and it’s probably not the best way for us to make decisions.

way we consume information about strength and conditioning, and it’s probably not the best way for us to make decisions. We see something on Instagram from someone with a bunch of followers, and we instantly think it must be the truth instead of digging deeper, doing our own research and getting the whole story. So, whether it’s politics or strength & conditioning, it’s important to get the whole story before you make a decision.

We see something on Instagram from someone with a bunch of followers, and we instantly think it must be the truth instead of digging deeper, doing our own research and getting the whole story. So, whether it’s politics or strength & conditioning, it’s important to get the whole story before you make a decision. sources of information. Of course, I use social media, but I also go to scientific journals, I take courses, I have multiple degrees, I read lots of books, I attend conferences, and I go to people who have many years of experience in the industry who put out quality information and who are in the trenches daily. These people have been doing it for years, documenting the results, analyzing their experiences and their programs, and then making decisions based on those analytics.

sources of information. Of course, I use social media, but I also go to scientific journals, I take courses, I have multiple degrees, I read lots of books, I attend conferences, and I go to people who have many years of experience in the industry who put out quality information and who are in the trenches daily. These people have been doing it for years, documenting the results, analyzing their experiences and their programs, and then making decisions based on those analytics. Along with the effectiveness of a training stimulus, you have to weigh the risk vs. benefit to help determine whether it’s the right choice to include in a program. For example, when I see kids standing on stability balls or doing circus tricks, I feel like the training benefit is incredibly small while the risk is fairly high. Or, I’ll see kids stacking a bunch of plates up on top of boxes to see how high they can jump. Again, the training benefit of jumping onto a box is no greater than jumping in the air as high as you can and landing on the ground, but the risk is MUCH greater. So, I personally don’t feel like the risk outweighs the benefit.

Along with the effectiveness of a training stimulus, you have to weigh the risk vs. benefit to help determine whether it’s the right choice to include in a program. For example, when I see kids standing on stability balls or doing circus tricks, I feel like the training benefit is incredibly small while the risk is fairly high. Or, I’ll see kids stacking a bunch of plates up on top of boxes to see how high they can jump. Again, the training benefit of jumping onto a box is no greater than jumping in the air as high as you can and landing on the ground, but the risk is MUCH greater. So, I personally don’t feel like the risk outweighs the benefit. Coaches may recognize an exaggerated arch in the lower back, but that’s just one part of the equation. The ability to control anterior and posterior pelvic tilt is critical to sprinting, squatting, hinging, and a variety of athletic movements. Many athletes struggle with these movements because they simply don’t know how to create or control pelvic tilt.

Coaches may recognize an exaggerated arch in the lower back, but that’s just one part of the equation. The ability to control anterior and posterior pelvic tilt is critical to sprinting, squatting, hinging, and a variety of athletic movements. Many athletes struggle with these movements because they simply don’t know how to create or control pelvic tilt.

When it comes to the squat, the deficits are typically the knees moving forward excessively as well as moving inward.

When it comes to the squat, the deficits are typically the knees moving forward excessively as well as moving inward.

Continuing our Top 3 series from Jordan Tingman, these are her Top 3 Core Exercise Variations.

Continuing our Top 3 series from Jordan Tingman, these are her Top 3 Core Exercise Variations.

understand that some of these may be done by other coaches, and while I respect other coaches opinions, this article outlines how I personally like to coach these exercises.

understand that some of these may be done by other coaches, and while I respect other coaches opinions, this article outlines how I personally like to coach these exercises.

conditioning coaches to receive push-back from people trying to vilify exercises in their program, with the squat being the target of the attacks. Whether it be sport coaches, athletic trainers, administrators, parents, or even athletes themselves, the squat is always surrounded by questions and opinions. It has been blamed for unrelated issues it hasn’t caused and even termed “dangerous” for reasons that many don’t know nor care to find out. To learn where all of this came from, it’s important to understand the history of the squat in America and how one particular researcher sparked a debate that continues today.

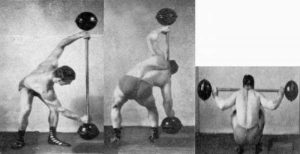

conditioning coaches to receive push-back from people trying to vilify exercises in their program, with the squat being the target of the attacks. Whether it be sport coaches, athletic trainers, administrators, parents, or even athletes themselves, the squat is always surrounded by questions and opinions. It has been blamed for unrelated issues it hasn’t caused and even termed “dangerous” for reasons that many don’t know nor care to find out. To learn where all of this came from, it’s important to understand the history of the squat in America and how one particular researcher sparked a debate that continues today. were quite impressive, even by today’s standards. While Steinborn is notable for many reasons, it’s the way in which he performed the squat that will still shock many lifters today. Steinborn performed squat sets, as heavy as 550 pounds for 5 repetitions, without having any supports, wraps and most remarkably, no access to a squat rack. He simply stood the barbell up tall on one end, leaned under it and hoisted it across his shoulders. This style of squatting is aptly known as the “Steinborn Squat”.

were quite impressive, even by today’s standards. While Steinborn is notable for many reasons, it’s the way in which he performed the squat that will still shock many lifters today. Steinborn performed squat sets, as heavy as 550 pounds for 5 repetitions, without having any supports, wraps and most remarkably, no access to a squat rack. He simply stood the barbell up tall on one end, leaned under it and hoisted it across his shoulders. This style of squatting is aptly known as the “Steinborn Squat”.

squatting. A letter sent to Klein from the US Marine Corps stated: “Our consultants agree that the type of exercise you condemn should probably be eliminated from physical conditioning programs.” The Army physical fitness test omitted anything that resembled a squat, and until recently, stayed the same for decades. While Klein had convinced many communities that the squat did more harm than good, there was still a strong contingency of professionals that saw Klein’s study as more subjective than objective.

squatting. A letter sent to Klein from the US Marine Corps stated: “Our consultants agree that the type of exercise you condemn should probably be eliminated from physical conditioning programs.” The Army physical fitness test omitted anything that resembled a squat, and until recently, stayed the same for decades. While Klein had convinced many communities that the squat did more harm than good, there was still a strong contingency of professionals that saw Klein’s study as more subjective than objective.

Many high school and college-level athletes feel like they either need to get as big and strong as possible or they don’t value it at all. Some of that depends on the sport they play, and some depends on their environment or what their coaches value. We need to help athletes put strength/size into perspective, and teach them that these qualities should be developed as a PART of their overall development. In some cases, it’s a small part, and in other cases, it’s more important. But, concentrating ALL of your effort on lifting weights if usually not what athletes need.

Many high school and college-level athletes feel like they either need to get as big and strong as possible or they don’t value it at all. Some of that depends on the sport they play, and some depends on their environment or what their coaches value. We need to help athletes put strength/size into perspective, and teach them that these qualities should be developed as a PART of their overall development. In some cases, it’s a small part, and in other cases, it’s more important. But, concentrating ALL of your effort on lifting weights if usually not what athletes need.

A highly athletic, low-skilled soccer player can easily get into position to make a play, but may not be able to take full advantage of the opportunity because of the low technical skills. On the other hand, a highly-skilled, low-athleticism player can control the ball, but won’t be able to get into position where their skills can best be utilized.

A highly athletic, low-skilled soccer player can easily get into position to make a play, but may not be able to take full advantage of the opportunity because of the low technical skills. On the other hand, a highly-skilled, low-athleticism player can control the ball, but won’t be able to get into position where their skills can best be utilized.