The squat is often considered the most important exercise an athlete can perform in the weight room. It’s frequently performed by world-class athletes, the most novice of lifters, and everyone in between. Strength and conditioning professionals have long relied on the squat, and its variations, as a cornerstone of their programs, but its acceptance has not always been well received outside of S&C circles. It’s not uncommon for strength and  conditioning coaches to receive push-back from people trying to vilify exercises in their program, with the squat being the target of the attacks. Whether it be sport coaches, athletic trainers, administrators, parents, or even athletes themselves, the squat is always surrounded by questions and opinions. It has been blamed for unrelated issues it hasn’t caused and even termed “dangerous” for reasons that many don’t know nor care to find out. To learn where all of this came from, it’s important to understand the history of the squat in America and how one particular researcher sparked a debate that continues today.

conditioning coaches to receive push-back from people trying to vilify exercises in their program, with the squat being the target of the attacks. Whether it be sport coaches, athletic trainers, administrators, parents, or even athletes themselves, the squat is always surrounded by questions and opinions. It has been blamed for unrelated issues it hasn’t caused and even termed “dangerous” for reasons that many don’t know nor care to find out. To learn where all of this came from, it’s important to understand the history of the squat in America and how one particular researcher sparked a debate that continues today.

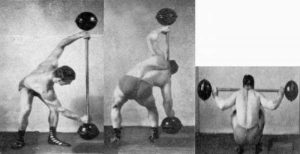

One would be remiss to discuss the history of squats in America without mentioning the name Henry “Milo” Steinborn. Steinborn is often credited with popularizing the squat in America. Prior to his arrival in 1921, the popular lifts in America were known as “power-type” exercises and consisted of lifts like bent presses, deadlifts, two-arm presses, and curls. After arriving in America, he quickly helped popularize the “speed’ and “quick” lifts that were more commonly performed on European shores. Among these lifts was the squat. Steinborn quickly garnered attention in the public eye by performing heavy lifts that  were quite impressive, even by today’s standards. While Steinborn is notable for many reasons, it’s the way in which he performed the squat that will still shock many lifters today. Steinborn performed squat sets, as heavy as 550 pounds for 5 repetitions, without having any supports, wraps and most remarkably, no access to a squat rack. He simply stood the barbell up tall on one end, leaned under it and hoisted it across his shoulders. This style of squatting is aptly known as the “Steinborn Squat”.

were quite impressive, even by today’s standards. While Steinborn is notable for many reasons, it’s the way in which he performed the squat that will still shock many lifters today. Steinborn performed squat sets, as heavy as 550 pounds for 5 repetitions, without having any supports, wraps and most remarkably, no access to a squat rack. He simply stood the barbell up tall on one end, leaned under it and hoisted it across his shoulders. This style of squatting is aptly known as the “Steinborn Squat”.

While Steinborn helped bring the squat to America in the 1920s, it wasn’t until the 1950s where it became widely performed by weightlifters. Up to that point, the split stance was more commonly used to lift heavier loads. The squat was used, but more as a supplementary lift to help build leg strength. After 1950 the “odd-lifts,” which are now known today as the power-lifts, became vastly popular. Squatting, of course, became one of the main lifts. Lastly, those who performed what we now think of as the Olympic lifts used split stance squatting as their main method of lower body training because the rules dictated that a lifter could not come in contact with the bar during the lift. The rules changed in the early 1960s and thus the squat style of Olympic weightlifting took over as the predominant method as it was easier to perform heavier loads and was much more efficient.

By the early 1960s, the majority of Americans still did not partake in resistance training. The small minority who actually lifted weights were most likely bodybuilders, Olympic weightlifters, and odd-lift/power-lifters. Very few athletes who participated in mainstream sports lifted weights at that time. It was actually feared that it would make them bulky, slower and less competent at their respective sport. Outside of the fear of being a performance decrement, lifting weights and performing the squat specifically was thought to be harmful.

Around that time, K. Karl Klein, a corrective therapist, led the crusade hoping to prove that squats were harmful to the body and led to an increased risk of injury. His rationale being that full depth squats would actually stretch the ligaments of the knee, making them more “lax” and thus more susceptible to significant injury.

While enrolled as a graduate student in 1959, Klein conducted a study that altered the public’s perception of the squat for decades. Klein’s study featured 128 experienced weightlifters who included full squats as a part of their training regiment, as well as 386 subjects who did not lift weights or perform squats of any sort. Klein’s study utilized a device that was built by Klein himself and was supposed to “objectively” measure the amount of medial or lateral “give” within the knee. The device was designed to brace the lower limb/shin region while the upper portion stabilized the quadriceps giving Klein the ability to manipulate the MCL and LCL manually.

After following up on his thesis, Klein published a series of articles on his research that concluded: “Full squats (where the top of the thigh is below parallel of the floor) damages the knee by stretching the knee ligaments.” His recommendation thus became: “No more than ½ squat should be used. In squatting the thighs should be slightly less than parallel.” His study and recommendation went on to be published in some of the most recognized journals for not only coaches but medical professionals as well. Publications such as Scholastic Coach, Texas Coach, Coach & Athlete, as well as The American Journal of Surgery featured Klein’s study.

Klein’s findings led many groups to deem the squat dangerous and thus unnecessary. Sport coaches saw it as a confirmation that lifting weights, in general, would make their players muscle-bound, and become slower, less flexible, immobile and more susceptible to injury. The medical community deemed it harmful and orthopedic surgeons and physical therapists, in particular, vilified the movement. Even the US military had a negative view of  squatting. A letter sent to Klein from the US Marine Corps stated: “Our consultants agree that the type of exercise you condemn should probably be eliminated from physical conditioning programs.” The Army physical fitness test omitted anything that resembled a squat, and until recently, stayed the same for decades. While Klein had convinced many communities that the squat did more harm than good, there was still a strong contingency of professionals that saw Klein’s study as more subjective than objective.

squatting. A letter sent to Klein from the US Marine Corps stated: “Our consultants agree that the type of exercise you condemn should probably be eliminated from physical conditioning programs.” The Army physical fitness test omitted anything that resembled a squat, and until recently, stayed the same for decades. While Klein had convinced many communities that the squat did more harm than good, there was still a strong contingency of professionals that saw Klein’s study as more subjective than objective.

As the years started to pass, new researchers began to conduct studies to determine if Klein’s claims were in fact true. With improved technology and a better anatomical understanding, the results began pouring in that in fact, Klein’s stance on the squat was incorrect. Between the 1960s and through the 1990s, researchers were coming to the agreement that squatting (and deep squats where the femur was below parallel to the floor) did not cause laxity in the knee ligaments and were safe to perform. These findings led to position papers put out by the NSCA and ACSM to help dispel the negative connotations that were set decades prior.

The Position Paper by the NSCA (1993 Chandler & Stone) states: “There is no objective evidence that full squats are harmful to the ligaments of the knee or the patellofemoral joint. When done correctly and under the supervision of a strength and conditioning specialist the full squat is safe and beneficial to athletic endeavors.”

The Position paper of the ACSM states: “In summary, the squat exercise is important to many athletes because of its functionality and similarly to athletic movements. If appropriate guidelines are followed, the squat is a safe exercise for individuals without a previous history of injuries. The squat is a large muscle-mass exercise and has excellent potential for adding lean muscle mass with properly prescribed exercise.”

Negative perception of the squat still exists to this day, and much of that perception can be traced back to a singular study performed by a graduate student in the late 1950s. By providing factual based evidence and understanding where the misconception arose so many years ago, strength and conditioning coaches can better defend the movements, including the squat, that they use in their program. The best way to defend a program is by educating. Continuing to do so will assist in showing others the benefit that a properly performed training program has in the world of athletics.

Joe Powell is an Assistant Strength & Conditioning Coach for football at Michigan State University. He held a similar position at Utah State University and has been an advisor to the IYCA for several years. Before his stint at Utah State, Joe was an Asst. S & C Coach at Central Michigan University where he also taught classes in the Department of Health and Human Performance. Joe is a regular contributor to the IYCA Insiders program and is one of 20 strength coaches who helped create the High School Strength & Conditioning Specialist Certification. Join IYCA Insiders or get the HSSCS to learn more from Joe.