Did you know that PLAY in and of itself has incredible health an cognitive benefits?

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, “research demonstrates that developmentally appropriate play with parents/caregivers and peers is a singular opportunity to promote the social-emotional, cognitive, language, and self-regulation skills that build executive function and a prosocial brain. Furthermore, play supports the formation of the safe, stable, and nurturing relationships with all caregivers that children need to thrive.”

Play is not frivolous!! It’s essential to development and even as adults, we need it!

Below you will find easy ‘printable’ concepts and tips to keep handy that represent the different kinds of play and the ‘ways to play’ within them!

Gameplay

Game Play is a mix of Movement play and Cooperative play, It helps children hone social skills as they figure out how to navigate group & family dynamics. It helps them learn how to collaborate and compromise with others, recognize and respond to others’ feelings, share, show affection, resolve conflicts, and adhere to the rules.

It can also help to strengthen the body and develop gross motor skills by offering opportunities in adaptability, flexibility, and resistance. Games can support advancements in physical developmental milestones, including coordination, stability, muscle development, body awareness, hand-eye coordination/control, balance, and fine and gross motor skills.

Ways to (Game)play (Pick something different each day!)

- Old School Games-Tag, Hopscotch, 4-Square, Wall Ball, Hide and Seek, Charades, Balloon Tennis, Bowling

- Relay Game/races (with friends or family) using different moves, like running, skipping, shuffling, backpedaling, hopping, carrying items, object-fill-a-container, dress up/out, building)

- Side-Walk Chalk Obstacle Course (draw a ‘course’ to ‘run, crawl, skip, hop, leap, etc’ through. Add ‘stations’ with different activities for everyone to do (like jumping jacks, crazy dances, pushups, etc)

- Indoor Obstacle Courses (crawl, run, jump, skip, stairs, bed-jumping, cushion-forts…they all count!)

- Sports Games (all count- but NOT structured- keep it agile and inventive)

- Body imitation games (simon says/copycat)

- Listening Games (redlight-greenlight/simon says)

- Board & Card Games

- Video Games (but you must play WITH them!)

*Modifications can connect us more fully with our player by finding the “Just-Right-Challenge” between being a bit of challenge, yet keep interest, but achievable (even with some support.)

There is so much to be gained if the focus is on the process, not the outcome! Therefore, allow for some time to “fail-safely”, refigure a plan and try again!

Free Play

Free play is when children have full freedom to play in whatever way they wish. “They can choose everything – they have the freedom to select their play materials, interest area and even the plot”. During free play time, children can express themselves in the way that they choose depending on the day, time and situation they are in. Free play, is just that…FREE, not to mention…FUN!

Ways to (free)play: Do daily!

- Do it YOUR way! There is no right or wrong here, get creative, let kids create their own ways to play and spend time connecting with their creations! If you need some ideas, browse the other ‘ways to play’, This is a great day to incorporate all the fundamental movement patterns that are so important at every age. They are, rudimentary locomotor (e.g., running, jumping, hopping, leaping) and object manipulation/control (e.g., throwing, catching, striking, kicking)

- The key to this type of play is to encourage their thought process, NOT provide them the ANSWER. This means, if they are building a fort, and you can see it is going to fall or not achieve what they are hoping, we can try it their way and help them “wonder” why it didn’t work the way they thought. “WONDERING” is the greatest skill here, and walking through the plan – whether it is about the rules or making mud a certain consistency, or getting a ball through a tunnel, or making an obstacle course- walk through the process WITH them, and help them refigure a new plan to met the goal.

THE FUN IS FINDING OUT WHAT WORKS WELL and LAUGHING WHEN IT DOESN’T – TOGETHER!!

- How to make this successful: Offer a variety of items to play with.

This can include access to things like; bikes, swings, sand boxes, water/sensory tables, couch cushions, blankets, chairs, pillows, empty large boxes, buckets, measuring cups/shifters, painters tape, pool noodles, jump ropes, frisbees/plastic plates/cups, chalk, pipe cleaners, markers, and natural things, dirt, leaves, rocks, sticks, water. These can allow for endless types of imaginative play themes.

*Oftentimes, play emulates real life. If you are stuck on a theme, use roles or experiences that have already been experienced- restaurant, school, occupations/bakers/police/dog catcher/builder. In this way the player gets to try on these roles and can be as silly or as serious as they write the script.

Nature Play

Nature play gives children the opportunity to explore and understand nature. From watching worms in the soil to balancing on a log, nature play is child-initiated and child-directed. Research shows that children benefit greatly from daily connections with nature.

The use of nature-based products in our play environments allow children to learn and develop responsibility as they care for plants and experience the natural world. Just like a classroom is carefully prepared by a teacher for learning, an outdoor play environment is carefully designed, beckoning the child’s innate desire to learn and explore.

Research indicates that, when children play and learn in nature, they do so with more vigor, engagement, imagination, and cooperation than in wholly artificial environments, and that symptoms of attention deficit and depression are reduced. Experts agree that children need access to nature the same way they need good nutrition and adequate sleep.

Ways to (Nature) play: Get outside daily

- Ponds, lakes, playgrounds, dirt, mud, water, logs, boulders, trees…explore the world today!

- Check out this AMAZING RESOURCE from the NATIONAL WILDLIFE FEDERATION!

- Hiking

- Exploring new territories

- Walking new trails and parks

- Identifying different animals & plants

- A nature scavenger hunt

- Recycled nature/natural product crafts

*If engaging in the environment presents some challenges, modifications can be made to present the material in smaller, more controlled ways. Consider providing items in small bins, for shorter periods of time, or provide a preferred item alongside the new items. Sometimes, providing a concrete goal, like “How many brown things can we find? 3 – Let’s do it”, can give purpose to the play as well as a firm ending to the new hard thing. Providing them some type of control and connection with us, makes the next time easier.

Constructive Play

Constructive play is a type of play that is designed to help children learn new skills, advance their development, and develop social skills. It can be achieved with other children or adults and can last anywhere from 10 minutes to an hour.

When playing with others, this kind of play helps children learn about social relationships and the importance of cooperation. It also promotes problem-solving skills, abilities and strategies as well as communication.

Ways to (constructive) Play: Incorporate a couple times a week

- Putting together a toy train track

- Building a blanket or couch cushion fort or in nature with sticks, logs and rocks

- Creating box constructions with recycled materials

- A pull apart activity table

- Building sand castles

- Digging dams and rivers in mud

- Creating with playdough

- Exploring loose materials

- Woodworking

- Sewing / Looms / Latch-HooK / Knitting

- Painting / Paint by Number / Fingerpaint / Shaving Cream/Pudding/Puffy Paint

- Building a marble run

- Create your own board games/Build a board game

- Lego building

- Recycled material building (Cardboard, cartons, bottles, cans)

- Crafts- Paper mosaics / Beadwork / sensory bottles / Leaf Rubbing Art

Creative Play

While “playing pretend” may seem like an insignificant form of play, it is an essential part of a child’s daily curriculum. Creative play, also may be called Dramatic play, provides children with the opportunity to work through emotions, develop and learn important social skills, and develop expressive language. The effects are seen in the classroom as research shows there’s a correlation between creative play and better literacy and reading skills.

Art and music play enhance play environments by expanding the ways children can learn and explore their creativity in the world. Research shows the arts are critical in helping children develop self-expression and creativity. Art and music play also help to improve memory and brain power. Additionally, children develop a wider vocabulary as they express their ideas behind the art they create.

Ways to (Creative) Play: Incorporate a few times a week

- Dancing

- Yoga

- Meditation

- Playing Pretend/Imagining

- Dress Up

- Puppets

- Plays or Productions

- Art

- Painting

- Crafting

- Molding with clays/playdough

- Bead-work

- Drawing

- Story-writing

- Chalk-Play

- Yarn Play

- Sewing/Loom

*These can build on each other. Create the story, make the puppets or gather/make the costumes, and perform. Even video and create a production Billfold. There are endless ideas and endless combinations, which makes endless roles for everyone to take part in the best way they are able.

Social Play

Children learn best when they can work together. This is why playing with others is so important in playgrounds, on sports teams, etc. When children are playing together, they have more fun and can learn new things more easily.

They also learn how to work together as a team and stay safe.

Ways to (social) play: Incorporate a couple times per week

- Playground Play with family members/friends

- Playdates at different locations from nature trails to sports fields/tracks

- Spontaneous sports play (bring a bunch of balls to a playdate) with Friends/Family Members

- Scavenger Hunts with Friends/Family Members

- Sports Team Practice or Games

- Board Games with family/friends

- Card Games with family/friends

- Invite friends over to play all the different ways with their favorite games

*This type of play is for everyone, even those who socialize using a variety of ways to communicate. Again, it is a great way to be invested in the process, and work through helping everyone express themselves and have their ideas heard. This relies on taking time in the process and not the product, and creating connections at just the right pace and understanding with each player.

*Consider the use of visuals, either printed pictures or the items themselves, in your play.

Overall, visuals in play help support everyone’s understanding of the object of play. Visual can provide clarity of thoughts and creates a quick way to make choices. When people feel part of the conversation and are valued in making choices in play, it most importantly, strengthens the connection between players.

Sensory Play

Children develop the 7 important sensory abilities including sight, smell, touch, hearing, taste, vestibular and proprioception as they play.

Sensory play helps children improve self/body awareness and improve interaction with and make sense of the world that surrounds them. Sensory play can include all the tastes, smells, textures and so much more!

Ways to (sensory) play: Incorporate a couple times per week

- texture scavenger hunts

- cooking & baking

- taste test game- sweet, salty, sour, savory,

- ‘feely” boxes- guessing games with cooked spaghetti, cotton balls, rocks, buttons, pipe cleaners, etc

- “feely” match games- soft, hard, gritty, silky, shaggy, corduroy, metal, sticky, bumpy, smooth, etc

- science experiments

- Potions- mixing textures, hard, soft, crunchy, sandy, liquid, slimy,

- exploring positions in space (ie. swing/upside down, bouncing, pushing/pulling, rolling, riding, spinning)

- Use of seated or standing scooters, saucers, bikes, trampolines, tunnels, slides, merry-go-rounds, obstacle courses, climbers, see-saws, climbing walls, rolling/unrolling in a blanket, pulled on a blanket, sled, summersaults, cartwheels, ball pits, etc.

PLAY is powerful and I think we all can agree that kids are getting less and less of it in this digital age. Exploration & discovery are some of the greatest teachers when it comes to developing athletes and great students.

I hope that this guide serves you to remove some of the guesswork of ‘how to play more’ but more than anything, I hope it encourages you to get out there and have fun!

Julie Hatfield-Still

Brand Executive for the IYCA.

Julie is an Entrepreneur, CEO, Coach and Author.

She is founder of the Impact More Method for entrepreneurs and the Inner Game Framework for Athletes.

If you are a new coach or parent who wants more ideas about ways to play to develop athletic ability! Check our these 4 free games for performance from IYCA CEO Jim Kielbaso!

Enhancing In-Game Performance is incredibly important. In this blog we will discuss integrating speed with soccer skills and ultimately enhancing performance on the field.

Enhancing In-Game Performance is incredibly important. In this blog we will discuss integrating speed with soccer skills and ultimately enhancing performance on the field. Conclusion

Conclusion Beni is an IYCA Ambassador, Entrepreneur and CEO. He’s earned UEFA coaching badges and a BA in Physical Fitness & Sports Conditioning. He has professional experience across soccer, golf, and rugby, expanding programs in Texas and Ireland. He has founded GameLikeSoccerCoaching and BBsports Fitness and Nutrition.

Beni is an IYCA Ambassador, Entrepreneur and CEO. He’s earned UEFA coaching badges and a BA in Physical Fitness & Sports Conditioning. He has professional experience across soccer, golf, and rugby, expanding programs in Texas and Ireland. He has founded GameLikeSoccerCoaching and BBsports Fitness and Nutrition. Here’s how to apply these concepts to soccer:

Here’s how to apply these concepts to soccer: Have you ever wondered how to train athletes who never have an off-season? You aren’t alone, we received a great question from one of you, and we want to address it. In this blog we will dive into, Training athletes who never have an off-season

Have you ever wondered how to train athletes who never have an off-season? You aren’t alone, we received a great question from one of you, and we want to address it. In this blog we will dive into, Training athletes who never have an off-season Primary Objectives:

Primary Objectives: Karsten Jensen, MSc Exercise Physiology, a renowned figure in the field, has been assisting world-class and Olympic athletes from 27 different sports since 1993.

Karsten Jensen, MSc Exercise Physiology, a renowned figure in the field, has been assisting world-class and Olympic athletes from 27 different sports since 1993.

Tactical Speed

Tactical Speed Jim Kielbaso is the President of the IYCA and Owner of

Jim Kielbaso is the President of the IYCA and Owner of

Warm-Ups, why bother? Great question! In this blog I share 3 Massive Benefits of warm-ups.

Warm-Ups, why bother? Great question! In this blog I share 3 Massive Benefits of warm-ups. Massive Benefit #2: Reducing Injury Risk

Massive Benefit #2: Reducing Injury Risk

In this article we are discussing power development for athletes.

In this article we are discussing power development for athletes.

Are you looking to run effective sports practices?

Are you looking to run effective sports practices? This is Must-Have Handbook for every coach who desires to incorporate Long Term Athlete Development into their practices-

This is Must-Have Handbook for every coach who desires to incorporate Long Term Athlete Development into their practices-  Rotational Power Development for Hitting & Throwing Sports can be overlooked but it is extremely beneficial for sports like baseball, softball, football, track, basketball and many others.

Rotational Power Development for Hitting & Throwing Sports can be overlooked but it is extremely beneficial for sports like baseball, softball, football, track, basketball and many others. performance and injury prevention.

performance and injury prevention. MB Rotation/Scoop Toss

MB Rotation/Scoop Toss  As High School Strength and Conditioning coaches we often deal with larger group sizes, with only a sport coach or two to assist implementing our programs.

As High School Strength and Conditioning coaches we often deal with larger group sizes, with only a sport coach or two to assist implementing our programs.

Pogo Jumps are one of the best exercises to reduce ground contact time and get athletes used to popping into the ground and reproducing that force quickly in the upward direction.

Pogo Jumps are one of the best exercises to reduce ground contact time and get athletes used to popping into the ground and reproducing that force quickly in the upward direction.

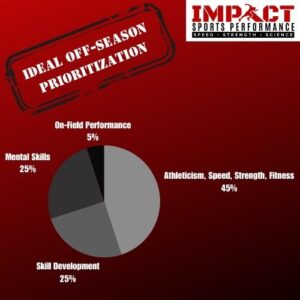

This is really the base, or foundation, for all athletes. While I know we could sit here and name off a dozen or so traits that could fall under this category, I think it’s best to narrow it down to a handful that I am sure we can agree make up the dominating percentage of athleticism. Those traits are:

This is really the base, or foundation, for all athletes. While I know we could sit here and name off a dozen or so traits that could fall under this category, I think it’s best to narrow it down to a handful that I am sure we can agree make up the dominating percentage of athleticism. Those traits are: The second stop on this journey through the Athletic Development Pathway is Strength, Speed, and Fitness. Just like General Athleticism, this CAN and SHOULD be trained throughout the entire year…yes even during the competition season.

The second stop on this journey through the Athletic Development Pathway is Strength, Speed, and Fitness. Just like General Athleticism, this CAN and SHOULD be trained throughout the entire year…yes even during the competition season.

As a coach, this is a very special pillar because we get to witness our athlete’s success and growth after all their hard work and time put into training. It is also where we will get a lot of feedback on what changed over the course of the training and what still needs work.

As a coach, this is a very special pillar because we get to witness our athlete’s success and growth after all their hard work and time put into training. It is also where we will get a lot of feedback on what changed over the course of the training and what still needs work. -Cole Walderzak-BS, HSSCS, CSAS, CSCS

-Cole Walderzak-BS, HSSCS, CSAS, CSCS

Acceleration can be defined as the rate of change of velocity in a movement. In coaching terms, it is how quickly an athlete can increase speed over a short distance (5-10 yds). So how do we get our athletes to be able to develop improved acceleration?

Acceleration can be defined as the rate of change of velocity in a movement. In coaching terms, it is how quickly an athlete can increase speed over a short distance (5-10 yds). So how do we get our athletes to be able to develop improved acceleration?