True athlete development and sport specialization is more than just year-round training and competition. It should be part of a comprehensive approach that involves both cognitive and physical development through childhood and adolescence. It should be a well thought-out, long-term pedagogic approach that fosters the acquisition of fundamental and sport specific skills while developing physical attributes such as speed, strength and endurance.

Unfortunately, a comprehensive, long-term approach is rarely implemented in youth sports. Instead, coaches and parents get distracted by trophies, elite clubs and early successes, and they lose sight of the end goal. This article will discuss a comprehensive approach to long-term development and sport specialization and dis-spell some of the misconceptions in athlete development.

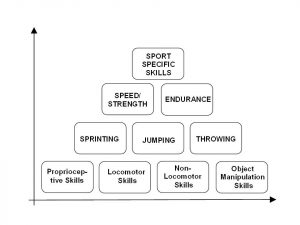

Fundamental motor skills start to emerge early in life and consolidate through childhood providing the playground for sport-specific skills to improve. Dr. Esther Thelen from Indiana University wrote about pre-adolescence as the “golden age of motor development,” representing a time for young and athletes to consolidate the foundation of movement while fostering the natural development of physical attributes such as strength, speed and endurance. Maria Montessori, a pioneer in the modern era of physical education said that “in the first three years of life, the foundations of both cognitive and physical development are laid.” Athleticism develops throughout childhood, moving from the spontaneous development of fundamental motor skills – walking, running/sprinting, jumping/landing, throwing/catching, striking, kicking and batting – to the acquisition of sport-specific skills and eventually mastery in sport. The process of learning new skills represents a fundamental component in developing young athletes.

Fundamental motor skills start to emerge early in life and consolidate through childhood providing the playground for sport-specific skills to improve. Dr. Esther Thelen from Indiana University wrote about pre-adolescence as the “golden age of motor development,” representing a time for young and athletes to consolidate the foundation of movement while fostering the natural development of physical attributes such as strength, speed and endurance. Maria Montessori, a pioneer in the modern era of physical education said that “in the first three years of life, the foundations of both cognitive and physical development are laid.” Athleticism develops throughout childhood, moving from the spontaneous development of fundamental motor skills – walking, running/sprinting, jumping/landing, throwing/catching, striking, kicking and batting – to the acquisition of sport-specific skills and eventually mastery in sport. The process of learning new skills represents a fundamental component in developing young athletes.

“Motor control significantly improves during childhood creating the foundation of a learning process that will eventually support the development of sport specific skills” (Blume, 1982). According to Jean Cote, one of the leading experts in the field of youth psychology, early sport specialization seems therefore to contradict the physiological process of growth and maturation taking place during childhood and adolescence, by limiting the opportunity to develop a wide, solid foundation of functional motricity.

According to Henkel (2010) the consolidation of basic motor patterns among children and pre-adolescent athletes provides the opportunity to acquire new motor skills. Fundamental motor skills foster the natural development of general coordination, static and dynamic balance, rhythm, and proprioception while fostering optimal physical development through a process known in the literature as “deliberate play.”

Based on the original taxonomy of motor skills described Antoinette Marie Gentile in 1972, these fundamental motor patterns include proprioceptive skills such as coordination, balance and rhythm, locomotor skills such as leaping, hopping, bouncing and skipping, non-locomotor skills such as bending, curling, turning and twisting, as well as object-control skills such as catching, kicking, throwing and tossing. Fundamental motor skills evolve from simple to complex, from discrete to serial and from closed to open skills as children “learn how to learn.” Motor control moves from general to specific according to the nature and the complexity of the movement in a learning process that evolves alongside with the physiological process of growth and maturation. For most young people, pre-adolescence is a time of heightened motor learning and development of general motor skills, and many physical improvements are attributed to neurological adaptation.

According to the youth sport specialization model described by Istvan Balyi and Ann Hamilton from the National Coaching Institute in British Columbia (Canada) pre-adolescent athletes should take full advantage of this time of intense motor learning by “acquiring general overall sports skills that are the cornerstone of all athletic development”.

Graph: Accommodation-Assimilation. The acquisition of sport specific skills throughout childhood and adolescence. The youth sport specialization model.

The acquisition of new skills represents, therefore, the endpoint of a process of assimilation and accommodation that bridges the gap between “learning to train” and “train to train.” This is the adaptation process described by Jean Piaget (1896-1980) as the “force driving the process of cognitive and physical development during childhood and adolescence”. Piaget described the first decade of life as a time of transition, or “a time of leaps and bounds” that reflects the effort of assimilating changes – both physical and cognitive changes – to accommodate a period of intense physical development.

In his “storm and stress theory,” G.H. Hall described the unpredictable sequence of physiological and psychological changes occurring during adolescence that affect the ability to tolerate stress, a key factor in the process of assimilating new skills.. Normative data has validated this model by describing what appears to be a common, predictable pattern of physical development for athletes through childhood and adolescence.

Cognitive skills rapidly develop after the age of three while physical attributes such as strength, speed and endurance follow a less predictable path that seems to suffer from a certain degree of discontinuity between times of intense linear growth (times of proceritas, from the Latin word procere meaning to increase in length ) and times of remarkable ponderal growth (turgor, from the Latin word turgere meaning to gain size). Such a discrepancy results in a temporary disruption (the storm) in what otherwise would be a continuous process of developing physical and cognitive skills.

| GROWTH, MATURATION AND PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT

Linear growth, ponderal growth and age-related physical development. |

|||

| AGE | MALE | FEMALE | PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT |

| 2-4 | Turgor Primus |

Fundamental Motor Skill Coordination

|

|

| 5-7 | Proceritas Prima | ||

| 7-9 |

Turgor Secundo |

Turgor Secundo | |

| 9-11 |

Proceritas Secunda |

Speed and Agility Anaerobic Power

|

|

| 11-13 |

Proceritas Secunda |

||

| 13-15 | Turgor Tertius | Relative Strength | |

| 15-17 | Turgor Tertius |

Adult Age |

Absolute Strength Aerobic Power |

| 17-21 | Adult Age | ||

Table: Growth, maturation and physical development. Linear growth, ponderal growth and age-related physical development.

It is not until peak height velocity (PHV), the apex of the physiological process of growth and maturation occurring between the age of 11 and 13, that the development of sport specific skills starts to match with the development of the fundamental physical attributes needed to compete in sport.

According to the youth physical development model described by Dr. Rhodri S. Lloyd and Dr. Jon L. Oliver from the Cardiff Metropolitan University (Wales, United Kingdom), the time that immediately follows PHV (sometimes referred to as the circa-pubertal phase) provides the perfect opportunity to introduce more structured, sport-specific training and competition.

Training effects before PHV seem to be mainly attributed to neurological components, while structural changes seem to occur after PHV when the endocrine response is greatly enhanced. It appears that there is laying effect that occurs during maturation, and that skipping the foundational development of general movement skills may lessen the ability to master more complex sports skills during maturation.

According to David Kirk from the University of Strathclyde (Glasgow, Scotland) “by focusing on the training process rather than the end product of it – competition – pre-adolescence represents a time to invest in the development of those physical attributes that are necessary to compete in sport.”

While all physical attributes seem to be trainable, the following appears to be the most appropriate general sequence of training focus and structure for most children (depending on the timing of PHV):

Ages 6-11: The focus will be on general motor development, speed/agility, and learning technical sports skills such as dribbling, shooting, etc. with relatively low structure in the training process.

Ages 11-13: Continue with speed/agility training and increase the time spent on relative strength/power. Competition, training volume and overall structure begin to slowly increase during this time. Sport specialization is considered and athletes may move toward this during this period.

Ages 13-16: Structure & competition increase and the development of strength and/or hypertrophy are introduced. Training volume continues to increase. Sport specialization often takes place during this time.

Ages 16-18: Structure & competition are heightened dramatically. Strength/power development and overall work-capacity can be more highly emphasized, and the volume of training increases as work capacity improves.

Based on this information, diversification, rather than specialization, seems to represent the most rational approach to develop young athletes. The consolidation of a solid foundation of functional motor development at an early age provides the best opportunity to acquire sport-specific skills alongside with the natural development of physical attributes such as speed, strength and endurance during maturation. Italian scientist Carlo Vittori once said: “Sport specialization is the rational, well-organized process of developing young athletes that moves from general to specific skills, from simple to complex tasks, in the effort to foster, rather than override, the physiological process of growth and maturation. Specialization should be the consequence, and not the meaning, of developing athleticism.”

of a solid foundation of functional motor development at an early age provides the best opportunity to acquire sport-specific skills alongside with the natural development of physical attributes such as speed, strength and endurance during maturation. Italian scientist Carlo Vittori once said: “Sport specialization is the rational, well-organized process of developing young athletes that moves from general to specific skills, from simple to complex tasks, in the effort to foster, rather than override, the physiological process of growth and maturation. Specialization should be the consequence, and not the meaning, of developing athleticism.”

When coaches/parents skip important steps in a young person’s development, the layering effect of physical development can be compromised, leading to sub-optimal development of athleticism and sport skills. By understanding this long-term approach to developing athleticism, we can potentially create greater long-term sporting success and do a much better job of implementing a true sport specialization strategy. This can help young athletes enjoy sports and achieve optimal results throughout the maturation process.

Antonio Squillante is the Director of Sports Performance at Velocity Sports Performance in Los Angeles, California. He is in charge of the youth development program which includes over 100 athletes 17 years old and under competing in many different sports. Antonio graduated summa cum laude from the University San Raffaele – Rome, Italy – with a Doctorate Degree in Exercise Science. He has worked in college and professional athletics, has written numerous articles and holds certifications from multiple organizations.

Antonio Squillante is the Director of Sports Performance at Velocity Sports Performance in Los Angeles, California. He is in charge of the youth development program which includes over 100 athletes 17 years old and under competing in many different sports. Antonio graduated summa cum laude from the University San Raffaele – Rome, Italy – with a Doctorate Degree in Exercise Science. He has worked in college and professional athletics, has written numerous articles and holds certifications from multiple organizations.

The IYCA Youth Fitness Specialist certification is the industry gold-standard for youth fitness and sports performance. Click on the image below to learn more about the YFS1 certification program.