Non-contact knee injuries in the female athlete: A practitioner’s desktop meta-analysis

By Dr. Toby Brooks, IYCA Director of Research and Education, Associate Professor, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center

This will be a bit of an abnormal article for me. My job is to regularly review pretty much every contribution that comes to or through the IYCA and to edit, approve, or in some cases reject any submission prior to publication in any and all of our available media channels. Consistently, I tell contributors to back claims up with peer-reviewed literature and to substantiate any controversial claims or pull them out altogether. I do the same with my students. Any claim based on scientific fact or published research should be identified and cited.

However, I wanted to veer from our normal course here just a bit and discuss a topic that is germane to many of our coaching membership: ACL injuries in female athletes.

The thing is, I thought it would be best to take the view from 30,000 feet. Rather than dissecting each and every study and determining how they might apply to the training and conditioning of young athletes, I thought it might be best to analyze the major themes that have emerged from the literature over the past three decades. And just to keep it interesting, I am not going to specifically cite one article. Those are for you to find.

We have long known that ACL injury rates among female athletes are significantly higher than their male counterparts. Many medical professionals suggest that females are anywhere between 2 and 10 times more likely to sustain an injury to the ACL that requires surgical management. Seven out of ten of those injuries are the result of a non-contact mechanism of injury. These are established, accepted facts. However, what is not as widely accepted or agreed upon is the reason for the disparity.

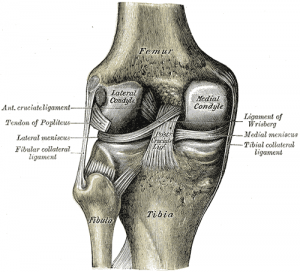

Intercondylar notch width, an anatomic variant, has been investigated. Endocrine-mediated factors have been investigated. The ACL actually has estrogen receptors that can, in theory, alter tensile strength depending upon where a female is in her menstrual cycle. Q-angle and the relationship of pelvic width to knee varus (“bow-leggedness”) or valgus (“knock-kneed”) have been examined. And lastly—and in my opinion most importantly—neuromuscular factors related to strength and proper landing mechanics have also been studied.

After more than a decade as an athletic trainer and strength and conditioning specialist working with athletes from middle school to professional sports, here’s my personal opinion: only one of those suggested mechanisms should really be of concern to the Youth Fitness Specialist: motor control.

And here’s why: it is the only one that is trainable.

All the other suggested sources for the differences between males and females—while fascinating—are scarcely alterable in a practical sense.

Notch width is what it is. No amount of intervention on my part as a coach is going to change that. The same goes for endocrine-mediated differences, too. I spent two years working with an NCAA Division 1 women’s gymnastics team. Trust me when I say if I could have intervened to reduce the influences of the semi-regular hormonal swings of the team (women who spend considerable time together tend to cycle together, in case you didn’t know. I didn’t until then.), I most certainly would have. Q-angle might be slightly modifiable if we get the athlete on an aggressive hip mobility program. But for the most part, those three potential sources provide little for the coach or YFS to do to truly intervene and minimize risk of injury.

On the other hand, neuromuscular control IS modifiable. Heck, it is what we who are blessed enough to get to work regularly with developing athletes are striving for in the vast majority of our training. An athlete who is weak and doesn’t yet know how to land properly is at risk of injury. The role of the ACL is to prevent the tibia from moving forward relative to the femur. It is what is referred to as a “static” restraint, meaning it does not require volitional control to get the ACL to do its job.

Before the ACL is ever called into action, the hamstring group functions as a “dynamic” restraint. Unfortunately, in full extension, the hamstring has next to no mechanical advantage through which to stabilize the tibia from moving forward. For example, the force vector of hamstring contraction in full knee extension is more likely to simply compress the joint rather than prevent anterior tibial translation.

However, if an athlete possesses adequate eccentric muscular control in the quads, glutes, and hams, landing with a “soft” flexed knee not only absorbs shock, it positions the knee such that hamstring contraction prevents the tibia from moving forward and thereby prevents the ACL from being loaded. As a result, landing with a flexed knee provides both dynamic AND static support. Unfortunately, landing with a “stiff” extended knee provides only static restraint. The ACL is effectively “hung out to dry” and the hamstring cannot effectively assist.

Case (or in this unfortunate example, cases) in point, two different NFL football players (1 & 2) have recently sustained season-ending ACL injuries due to the performance of a celebratory “sack dance” popularized in response to an insurance company’s “discount double check” ad campaign. Both athletes are world-class and undoubtedly have incredible hamstring strength. Strength is not the problem. However, when performing this move, both athletes landed from a jump with an extended (or at least extending) knee. Without the hamstring able to provide a first line of defense against anterior tibial translation, the duty fell to the ACL. In both cases, the ACL failed. In both cases, the athletes will undergo surgery and have been lost for the season.

So the bottom line for the YFS, whether working with young athletes, male athletes, female athletes, or some combination of the above, is to teach and train athletes to learn to land. Low-level plyometrics and simple motor control drills are critical. Strength is important, but strength without neural control is dormant and ineffective in the moment of potential injury.

Countless training resources have been developed to help train young athletes to prevent non-contact knee injuries. Dr. Frank Noyes of the Cincinnati Sports Medicine Foundation and physical therapist and researcher Holly Silvers of Santa Monica Sports Medicine Foundation have both spearheaded impressive efforts to change the way athletes train and even warm-up in order to protect them from injury.

So while other suggested reasons for the difference between male and female knee injury rates are interesting, none are as readily modifyable as neuromuscular control. And teaching a young female athlete how to land properly is probably one of the most important things you can do to protect her from injury.

So the next time you decide to celebrate a new client, an unexpected bonus, or some other fortuitous piece of information by cranking out a discount double check of your own, modify it slightly with a flexed knee. Teach your athletes to do the same; your anterior cruciates will thank you.

Fantastic article, that I can use now. I work with college age students, both males & females, and it’s frightening the amount of plyo they do with poor landing and control mechanics. Great applied info.

I am now on my 3rd ACL rupture (non contact) and so this article caught my attention. If there was a way I could help at least one young female athlete avoid this I would be thrilled. My ACL injuries were all complete ruptures but none were from “landing.” Ski racing at 17/18 yrs oldand a more recent (blame my lack of proper conditioning)rupt twist and turn playing soccer.

Most often as a young injured athlete I was told my quads were over proportionately strong in relation to my hamstrings which were extremely tight.

This made sense to me and PT and 12 months of specific training was done . 13 months later I did the same exact rupture to my other ACL.

So, if there is something more to give young female athletes then the feeling that it is really not in there control and just a matter of bad luck or a matter of time, that would be a gift!